With the sad news that Elgin Baylor passed away this week at age 86, I thought it would be nice to take portion of my dissertation where Baylor was given some shine. The story about Baylor is well known, as far as the 1950s NBA is concerned, but it’s worth retelling. I’m also including some of the dissertation that leads up to Baylor’s protest. Helps provide better context for what it was like being a Black player in the NBA at the time.

Below is the excerpt in all its unvarnished glory/agony.

Mirroring what other African Americans experienced integrating white neighborhoods, Lenny Wilkens and his wife Marilyn were the first Black family to move into the Moline Acres area of St. Louis in 1964. Immediately, “For Sale” signs appeared up and down the street. Wilkens sarcastically accosted the white people: “How insane to think that our presence would destroy the value of such properties. Some of them couldn’t get much worse than they were.”[1]

Wilkens also recalled two brushes of racism with his own team during his rookie season of 1960-61. After an exhibition game in Atlanta, Wilkens and a Black teammate were dining at a restaurant near a hotel the team was staying at. “While we were eating, one of our white teammates entered and sat at a table on the other side of the room, intently acting as if he didn’t know us.” Wilkens admitted this was a “slight thing, but an icy cut that leaves a scar deep down inside a man.” Another dispiriting moment was when Wilkens “re-encountered a white girl I had known when I was in college.” Working for an airline company, she would have coffee with Wilkens when the Hawks were at the St. Louis airport. Wayne Embry, a Black player for the Cincinnati Royals, called Wilkens “crazy.” Another Black player, Hawks teammate Woody Sauldsberry, told Wilkens one night that two of their white colleagues were not thrilled at the “fraternization.” Wilkens angrily recounted, “This fine woman is married today and I am her daughter’s godfather, just as she is the godmother of my eldest daughter, Leesha.” [2] Clearly he was not happy with some of the behavior exhibited by his white teammates.

Generally, though, Wilkens believed that athletes—Black and white—did not socialize much during the non-basketball season because each player was “preoccupied with what he is trying to accomplish that he simply doesn’t take the time, or seek out the opportunity, to discover his teammates.” An exception to this rule was Cliff Hagan, who Wilkens described as “brought up in the solid-South, exposed to the stereotype of black athletes: not too bright, reckless with money and attracted to glittery possessions.” His friendship with Hagan “developed not overnight but rather over a period of time” as the Kentucky-raised Hagan began asking “more and more questions[.]” Eventually the two, together with their wives, would go on trips around St. Louis. Exemplifying Hagan’s open-minded demeanor, a team function was hosted at announcer Buddy Blattner’s home. Wilkens told Hagan he had no idea where Blattner’s house was. “I do,” Hagan responded. “Stop by my place and we’ll go together.” Sihugo Green, another Black player, also showed up before Hagan drove the two over to Blattner’s home.[3]

Obviously, the kindness and curiosity showed by Hagan was sometimes absent from other white teammates and generally not reciprocated by white society. The avalanche of racism came from nearly every conceivable corner.

Bill Russell recalled a 1966 phone conversation with a white advertisement executive looking to contract Russell for an endorsement deal. Following an underwhelming financial offer, Russell demurred on doing the ad. The executive, sounding “huffy” according to Russell, persisted: “[T]here’s a considerable amount of money involved here, but most of the people we’ve talked to aren’t much concerned about the money. It’s a matter of prestige.” Russell snapped, “If I needed prestige, you wouldn’t have called me in the first place. The only reason you called me is that I already have prestige, and you want to rent it.”[4]

Wilt Chamberlain also wryly commented on the advertising world. He criticized the paucity of endorsement deals offered to Black players. “I’ve done pretty well,” he noted, but then tore into the disproportionate attention given to white athletes. “Hell, look at Mark Spitz. He must be doing a dozen TV commercials a day. They say those seven Olympic gold medals will mean $5 million to him. And swimming isn’t even that big a sport in this country.” Chamberlain went on. “If a white athlete has one or two great years, he’s practically set for life. Guys like Joe Namath and Tom Seaver get endorsements, business opportunities, the works. When they’re through with sports, they’ll still make good money. But most blacks are just used.”[5]

Encounters with the state, and its racist proxies, also abounded. Chet Walker was arrested in high school for “gambling” while playing blackjack for fun with his friends at a park after they had played recreational basketball. The arresting officer was Black and was “a real hard-ass” trying to prove to his white co-workers “that he could be as tough on black kids as any white cop.” Walker called it “part of a colonial mentality: identify with your oppressors, put on a uniform, and no one can get at you anymore.”[6]

Earl Monroe in October 1971 visited the ABA’s Indiana Pacers as a possible prelude to jumping leagues. After the game was over, Monroe was in the locker room congratulating Indiana for their win. Then, “after they had showered and dressed, all the black players reached up over their lockers and start[ed] bringing down guns. I was shocked to see this and asked, ‘Why do you guys have guns?’” The Black Pacers responded, “They got the Ku Klux Klan everywhere around here outside Indianapolis…. So we got guns to protect ourselves.”[7]

A form of violent self-defense prevailed on the court, too. Perhaps the overall lack of trouble from white players toward Black players was basketball’s generally more tolerant racial atmosphere when compared to other sports. Or it could have been that Black players could retaliate easily against whites who behaved inappropriately. After all, given the cramped quarters of a basketball court, some physical action may go unnoticed by referees and fans. With that in mind, Earl Lloyd told teammates—white or Black—that if they got trouble from an opponent, “Bring him my way.” As Lloyd rationalized, “You can’t just let other teams pound on your people. If you’re going to do that to one of our guys, you’re going to pay the price.” When George King, a white West Virginian, was being roughed up by an opponent one night, Lloyd let King know to “bring him my way.” “So George brought him to me, and I set the pick the certain way I had to set it, and the guy learned the lesson. He learned real quick.” In setting these picks, Lloyd described them as “you firm up your body, make it real taut, and you get ready and the ref is looking the other way, and then ‘Boom!,’ and maybe you add a little icing to it. You set a pick, and whatever juice you can add to it, you do it.” As Lloyd astutely noted, in baseball the individuals are isolated. Any violent retaliation from Jackie Robinson to opponents would be out in the open and easily decried. In basketball, the intermingling of players at all times could mask some of the hits. “I had that recourse,” Lloyd summarized. “Jackie didn’t.”[8]

3.2 CIVIL RIGHTS MEETS THE NBA

The ability to handle any on-court troubles still left matters off the court unresolved. Lloyd could not “pick” his way to equal accommodations. The pioneering Black players of the 1940s and early 1950s gave way to a new, more militant generation by the end of the 1950s. Emblematic of this more aggressive stance was superstar forward Elgin Baylor. Whereas most of the earlier Black men in the NBA were not star players, Baylor was immediately the attraction of the Minneapolis Lakers during the 1958-59 season. Just a rookie, Baylor made a very vocal and public protest against racism that was a landmark moment for the NBA.

The incident began in Charleston, West Virginia, on January 16, 1959. Lakers’ team captain Vern Mikkelsen was at a hotel front desk attempting to check the team into their rooms. The desk clerk informed Mikkelsen that the white players could stay; but not Baylor, Ed Fleming, and Alex “Boo” Ellis, who were all Black. Mikkelsen protested, as did coach John Kundla. Eventually, Kundla got team owner Bob Short on the phone to no avail. Some of basketball’s mightiest men had been thwarted by a bellhop. Admirably, Kundla refused to split his team up, so he had everyone stay at a Black hotel instead. Nonetheless, Baylor was rightfully angered by the incident, but still intended to play at the scheduled game that night until he was denied service at a restaurant before the game. That was the final straw. Although Fleming and Ellis took the court, Baylor sat out in protest.

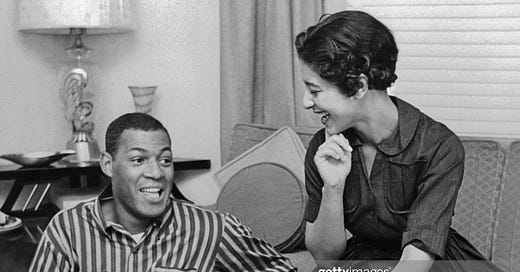

“It burned me up, that’s all,” Baylor told the Minneapolis Tribune two weeks after the incident. The Lakers’ all-star forward was not naïve about race. “I was in segregated high schools in Washington, D.C.” However, he attended college in Idaho and Washington State, where the flagrant Jim Crow attitude dissipated. “Ever since I went to college I’ve seen everybody as the same. I’ve never felt different since.” Showing that the new generation of Black players had higher expectations of the pro game than their predecessors of the 1940s, Baylor stated, “Segregation was a thing of the past. I’d forgotten things like that existed.” “There’s one thing about Elgin,” his then-wife, Ruby Saunder, told the Tribune. “Something’s right or wrong. He holds steadfastly to a principle. There’s no half way.”[9]

“His action stirred a debate throughout the sports page world,” Marion E. Jackson of the Alabama Tribune, a Black newspaper, wrote. Jackson chastised white people “who [can] enjoy the Negro’s talent,” but who can’t live with him as “strange and medieval[.]” H. Thomas Corrie, whose American Business Club sponsored the game in Charleston, angrily riffed that Baylor’s strike had “embarrassed” the Club and ruined the chances of Charleston hosting future NBA games. Jackson acerbically noted that Corrie made no mention of Baylor, Fleming, and Ellis being embarrassed by Jim Crow. Bob Short, who insisted he had been promised by the promoter that the Lakers would not endure segregation on the trip, declared, “From now on, unless we are guaranteed common facilities for rooming and feeding all our players we shall not appear in that city… And we will schedule neutral games only on a non-segregated basis.” The league followed up Short’s declaration with a policy for neutral-site games that “will insist on a clause to protect players and clubs from embarrassment.”[10]

Baylor’s protest also forced white players to confront aspects of the United States they were oblivious about. Rodney “Hot Rod” Hundley, born and raised in Charleston, was not the same after the incident. “It was supposed to be a big deal for me and I wanted all the guys on the team to be treated well and have a good time,” Hundley remembered. “I never thought there would be a racial problem, but you don’t think about those things when you’re white.” Sensing trouble from Baylor prior to the game, the local promoters sent Hundley to the locker room to convince Baylor to play. “What they did to you isn’t right,” Hundley acknowledged. “But we’re friends and this is my hometown. Play this one for me.” After Hundley’s appeal, Baylor stated, “Rod, you’re right. You are my friend.” More importantly, though, Baylor added, “I’m a human being, too. All I want to do is to be treated like a human being.” Only at that point could Hundley “begin to feel [Baylor’s] pain.” Hundley exited the locker room and told the promoters, “Elgin isn’t playing and I don’t blame him. He shouldn’t after how he was treated.”[11]

Despite Baylor’s strike in 1959 prompting NBA owners to declare they would not play any more games with segregated accommodations, the Boston Celtics’ exhibition trip in the fall of 1961 showed that the promise was easier made than kept.

And that’s the excerpt. Plenty more where that came from, but y’all ain’t ready to read 250 more pages of material.

Sources

[1] Lenny Wilkens, The Lenny Wilkens Story, 8.

[2] Lenny Wilkens, The Lenny Wilkens Story, 5-6.

[3] Lenny Wilkens, The Lenny Wilkens Story, 7.

[4] Bill Russell and Taylor Branch, Second Wind, 191-192.

[5] Wilt Chamberlain and David Shaw, Wilt, 53-54.

[6] Chet Walker with Chris Messenger, Long Time Coming, 47-48.

[7] Earl Monroe with Quincy Troupe, Earl the Pearl, 292-293.

[8] Earl Lloyd with Sean Kirst, Moonfixer, 91-92.

[9] Mercer Cross, “Elgin’s No Turkey at Pranks or Points,” Minneapolis Tribune, February 1, 1959.

[10] Marion E. Jackson, “Sports of the World,” Alabama Tribune, February 13, 1959.

[11] Hot Rod Hundley and Elgin Baylor as quoted in Loose Balls by Terry Pluto, 72-74.

Thank you for sharing this powerful excerpt from your dissertation. Getting ready for the other 250!!

This is awesome. Keep up the great work. Note that you have Hundley saying “dig deal”. I assume it’s supposed to be “big deal”. Good luck with the rest of your dissertation!