Building upon last week’s look at basketball’s original rules, today we’re checking out the ideology that produced the sport itself: Muscular Christianity.

I have a decent grasp on this religious outlook that infused basketball, but I wanted to bring in my friend Paul Putz, who has studied Christianity and sport far more deeply than I have. Paul’s a professor at Baylor University and an aficionado of the Kansas City - Omaha Kings. Emphasis on the Omaha part.

Alright, time for the riveting Q&A, which has been slightly edited in some places, between super cool academics. Imagine a bunch of tweed and elbow patches.

Q1: Hi Paul, I've known you for several years now, but could you tell the people about yourself? What drew you to study the connections between sports and Christianity?

I'm a historian who specializes in American sports and Christianity. I get to think and write about those two themes quite a bit in my current role as the Assistant Director of the Sports Ministry Program at Baylor's Truett Seminary.

As for the origins of my interest, I'm one of those academics who got into a subject for autobiographical reasons. I grew up in Nebraska where sports and faith are closely intertwined (I've written a bit about this before). One of the most important organizations in that space, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes [FCA], played a formative role in my life. When I began doing graduate work in history, my curiosity about the origins of the FCA began to grow. I knew from experience that the FCA was not just a club for Christian athletes; it was trying to form me into a particular type of person.

I wanted to know more about the cultural and theological values behind that work of moral formation: Where did they come from? How did they evolve? How did the FCA and other Christian ministries get embedded within sports? How much power and influence do those organizations have in American life? Six years later I’m still digging into those questions.

Q2: From my understanding Muscular Christianity emerged in the late 19th century. What is Muscular Christianity and why did it have such a prominent role in physical education and athletics at that moment?

Muscular Christianity has its origins in Britain in the 1840s, but you’re right to note that the late 19th century is when it really takes off in the United States.

[Ed. note: Paul has already corrected me. This is why I get outside help.]

It’s a nebulous movement, but what differentiates it from “ordinary” Christianity at the time is its emphasis on physicality, masculinity, and the body. Many Christians back then held on to this idea that to be the best Christian, one had to focus on the inner life, on things not seen: on cultivating the mind and the heart. In this view, the body is sort of a necessary evil, full of sinful desires that must be controlled by one’s inner self. So while physical labor might be necessary as part of one’s work, things like recreation, exercise, and sports are seen as time wasters because they don’t cultivate the soul and they can potentially lead to all sorts of fleshly desires.

Muscular Christianity comes along and says that Christians—especially male Christians—need to place a higher value on the physical body: they need to train it and exercise it so that they can put it to Christian service.

Maybe the best visual representation of this muscular Christian logic is the old logo of the Young Men’s Christian Association. In the late 19th century the YMCA becomes probably the leading organization spreading muscular Christian ideas. And it’s in the 1890s when the YMCA adopts its famous inverted triangle logo, with the three sides representing the unity of spirit, mind, and body that muscular Christians are trying to promote.

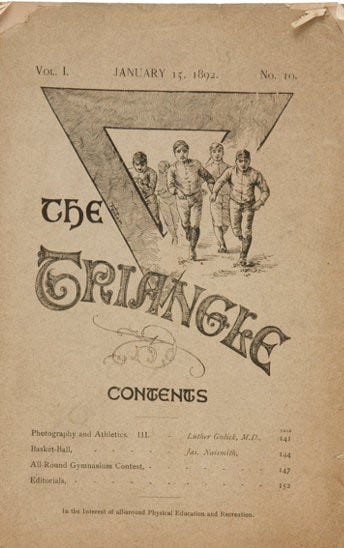

[Ed. note: The Triangle magazine from January 1892 mentioned in last week’s article. If you look closely, you can see James Naismith’s article debuting “Basket-Ball.” Editor of the magazine was Luther Gulick another monumental figure in early basketball.]

There are other defining features of muscular Christianity, too. It's a movement led primarily by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. And it's closely connected with nation and empire.

In the United States, it takes off in large part because there's both a growing fear of overcivilization in the late 19th century and a growing excitement about the possibility of national expansion. If white Protestants want to lead and take charge of the supposedly more “primitive” races—either overseas, in growing American cities, or in boarding schools for Native Americans—they need to be physically equipped for the task. But urbanization, industrialization, and corporate capitalism are taking white Protestants out of physically demanding jobs and into white-collar city work. Physical exertion can no longer be assumed as part of one’s daily existence, it must be intentionally sought out.

At the same time, muscular Christians believe that America’s leaders need to be morally equipped for their task—you know, the whole “White Man’s Burden” idea.

So along with trying to make Christian men more physical and athletic, they’re also trying to make physical and athletic men more Christian.

The problem with this is that for all of American history, women have been more involved in Protestant churches than men. Muscular Christians try to counter this feminine reputation by either bending over backwards to attract men to church or by trying to find ways to bring Protestant values to men outside the church.

That’s where we get to the importance of athletics. For muscular Christians, sports are seen as a natural way to appeal to men and to bring them into the church. But sports are also seen as a space where Christian values can be cultivated in young men. The key is to create the right conditions and institutions in sports for that sort of moral formation to occur.

As muscular Christians get more and more involved in athletics, they do two main things: First, they help to legitimize sports for church-goers, making it a more respectable activity instead of something seen as frivolous or even sinful. And second, they begin to shape the structures and systems of athletics in hopes of making sports in the United States a place where Protestant-approved moral formation can occur.

The influence of muscular Christianity on our entire sports infrastructure in the United States is really quite remarkable. If you take a look at the International YMCA Training School (now known as Springfield College) in 1890 you can get a glimpse of this. The physical education department of the school is led by Luther Gulick. He goes on to help create the first public high school sports league in the country (located in New York City), along with other youth-focused recreational programs. The football team, meanwhile, is led by Amos Alonzo Stagg, who later pioneers and develops the roles of full-time collegiate athletic director and football coach. And then there’s a physical education instructor named James Naismith.

Q3: If I'm not mistaken, Gulick is the one who comes up with the Triangle logo, right? In any case, Gulick was the taskmaster who set Naismith down the road of creating basketball. What role did basketball play in improving Muscular Christianity? How did it compare with other sports (football, baseball, etc) in that process?

Yes, that’s right, we can give Gulick credit for the Triangle logo.

As you note, basketball was invented out of necessity—it’s formed because Naismith’s boss gives him the job of creating a game to hold the attention of a group of unruly men. But along with the practical matter of making a game to please his boss, Naismith also believed basketball could provide strategic value to muscular Christians in a couple different ways. First, it could give them an indoor sport to play. With football dominating the fall and baseball the spring, basketball offered a sport for winter.

Second, Naismith believed basketball could help participants build character and develop skill and courage without the brutality of sports like rugby and football.

"If men will not be gentlemanly in their play, it is our place to encourage games that may be played by gentlemen in a manly way and show them that science is superior to brute force with a disregard for the feelings of others,” Naismith wrote when he introduced the game to the world in 1892.

This seems like a veiled shot at football, but Naismith never ditched the gridiron game. He came to football’s defense in the ensuing decades and saw it as vital to college life. Still, Naismith clearly believed that basketball could avoid the excesses of wanton brutality that too often occurred in football; it provided “personal contest without personal contact,” he would later write, while giving participants the chance to develop a variety of physical and moral traits.

If basketball offered a more refined version of manhood than the rugged aggression of football, compared to baseball it offered a sport that was more closely linked (at least at first) with amateur ideals. Although baseball was played at the college level, professional baseball was the most popular and prominent version. Baseball’s association with professionalism made it less appealing to muscular Christians as a character-building sport. And muscular Christians didn’t have much say in how baseball was run and organized. Thus, it was less common for muscular Christians to see baseball itself as a means of cultivating Christian values; they were more likely to use baseball’s popularity as an attention-getter for a religious message—to get a famous ballplayer to speak about faith or to advertise for the YMCA, that sort of thing.

Beyond what Naismith intended for basketball, if we look at the historical development of the sport I think there are two crucial ways that the game expands the reach and influence of muscular Christianity. First, basketball reflects muscular Christianity’s global and imperialistic dimensions. The YMCA was an international organization, with missionaries attempting to spread Christianity (of a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant sort). Because basketball was invented at a YMCA training school, it’s embraced and used by YMCA workers stationed around the world.

American football never gets a foothold outside of North America. But in part because of its close association with the YMCA, basketball does.

[Ed. note: this is an important point in the history of basketball. It didn’t magically become “international” with the Dream Team in 1992. YMCA educators and missionaries were spreading the game far overseas in the 1890s.]

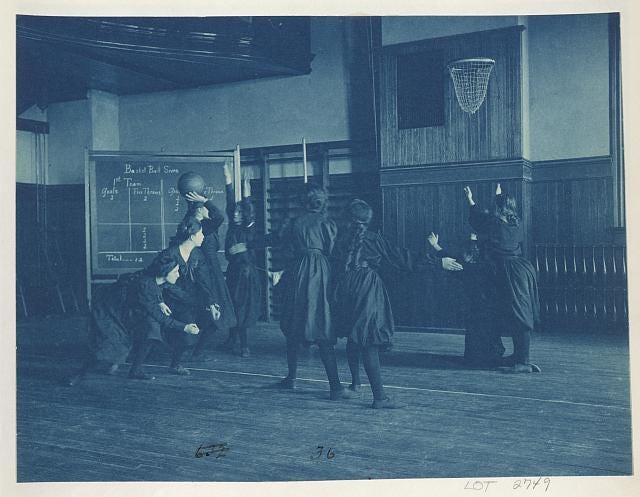

Second, unlike baseball and football, basketball was quickly picked up by women. This happened soon after its invention when Senda Berenson, the director of physical education at Smith College, modified the game and brought it to her students. It caught on at women’s colleges across the country. Berenson was Jewish, so clearly muscular Christians were not the only constituency interested in moral formation through sports.

In 1894, Berenson wrote an article explaining how and why she adapted the sport for her students, and she framed it with a similar logic used by muscular Christians. If sports were so good at developing positive traits in men, she noted, why couldn’t sports do the same for women? "By developing her body by as scientific and thorough means as her mind,” Berenson wrote, women could "reach the highest development of true womanhood."

Berenson and other women who picked up basketball were still constrained by gendered norms and expectations that limited their opportunities in athletics. Still, basketball became one of the few competitive team sports available for women, and thus one of the ways in which muscular Christianity extended beyond men.

[Ed. note: girls playing basketball in Washington, DC, in 1899. Note the peach basket has been ditched, yet the net is not yet open at the bottom. Library of Congress.]

Q4: I've seen up close at the YMCA Archives at the University of Minnesota some of the opinions Muscular Christians and YMCA officials had about professional sports. Their critiques of pro sports were often explicitly full of class politics, racism, and xenophobia. They were also very concerned with enforcing a firewall between amateurism and professionalism. What are some of the tensions you've seen between Muscular Christians and professionalized sports, particularly basketball?

Earlier I mentioned that muscular Christians wanted to shape the structures and institutions of sports so that moral formation could occur through athletics. Amateurism was central to that project, both because amateur sports were supposedly freer from the vices associated with pro sports—gambling, drinking, swearing, etc.—and because many muscular Christians were idealistic believers in amateurism as an ideology.

The obvious and blatant hypocrisies of “amateur” American sports probably limit our ability to understand amateurism’s original allure. One comparison that might be helpful is to consider the way some people think about art—painting, music, writing, etc.. There’s a long history of believing that “true” art, the “best” art, must be free of commercialism or the desire for money. If an artist creates out of a desire for money, the thought goes, then whatever the artists creates will be tainted.

In a somewhat similar way, proponents of amateur sports believed that an athlete’s motivations were the key to unlocking the character-building potential of sports. Playing sports out of a love for the game, for one’s teammates, or for one’s community or school were viewed as good motivations; these would help to build traits of loyalty, sacrifice, and cooperation. But playing in order to make money, win acclaim, or for other supposedly selfish reasons corrupted the idealism that made sport an engine of positive moral formation.

By maintaining a firewall between amateurism and professionalism, muscular Christians believed they were protecting the potential for moral formation through sports.

Now, embedded within this idealistic view of sports were all sorts class- and race-based assumptions and prejudices. Only athletes who did not need to earn money for themselves or their family could participate in athletics organized around the amateur ideal. So amateurism conveniently set up the middle- and upper-class white Protestants of muscular Christianity as the guardians of morally “pure” athletics.

Meanwhile, there were muscular Christian coaches like Amos Alonzo Stagg who on the one hand insisted on preserving amateur principles for athletes while on the other hand building a highly commercialized football program and also capitalizing on his fame as a coach to make more money.

Basketball was part of the debate over amateur and professional sports, especially in its first couple decades as YMCA leaders tried to maintain control over the game. But basketball was not as prominent in public debates about amateurism, at least not compared to football. Although basketball was growing in popularity, for the first half of the twentieth century it lagged far behind sports like football, baseball, and boxing in terms of national attention and popularity.

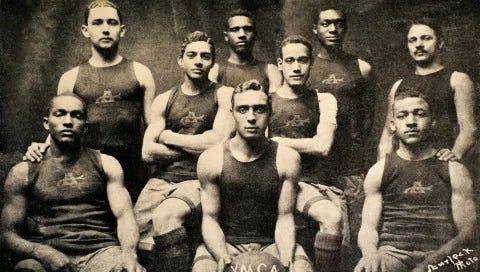

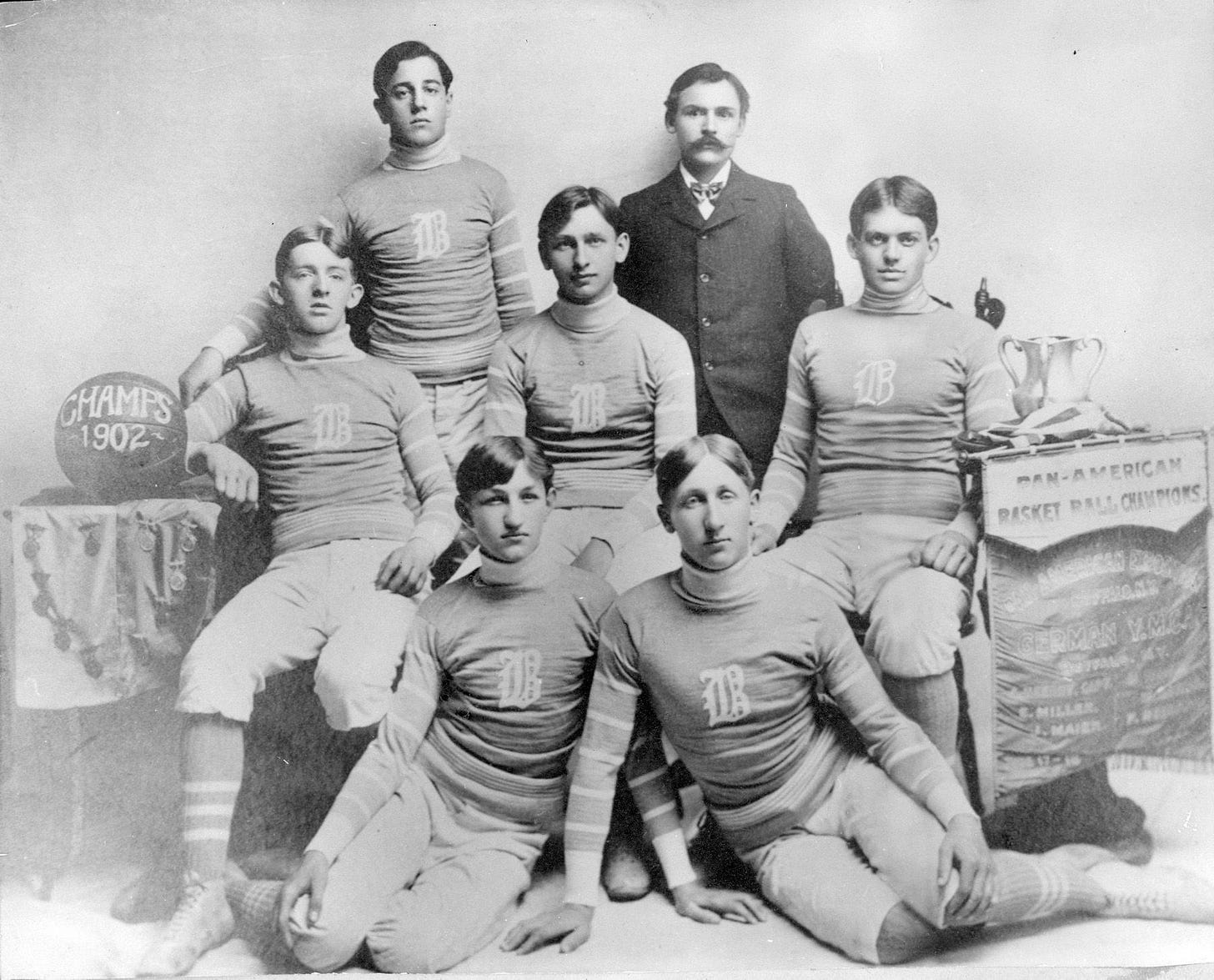

[ed. note: many of the first professional basketball players and teams emerged from amateur YMCAs. The Buffalo Germans, pictured above, were perhaps the most famous of these early amateur-turned-pro hoopsters.]

And basketball, too, as it evolved, moved away from the guardianship of its muscular Christian origins. It became a popular city game, associated with Irish, Jewish, and Black communities that didn’t fit the white Protestant muscular Christian mold. And it also became popular in rural and small-town communities in states like Kansas and Indiana. These places had plenty of white Protestants, but they tended to lean more towards George F. Babbitt booster-types than the elite Ivy Leaguers who thought they were above vulgar commercialism. This is why you can have someone like John Wooden—a small-town Indiana boy who idolized Amos Alonzo Stagg—play pro basketball in the 1930s after his college career was done, with no apparent reservations.

It is interesting, too, to consider how the founder of basketball’s views on amateurism evolve over time. James Naismith was undoubtedly a proponent of amateur sports; even at the end of his life he thought the college game superior to the professional. But he was also able to recognize the hypocrisy of the amateur system as it came to exist in college sports. In 1925 there was a big national scandal when college football star Red Grange turned pro. Defenders of amateur athletics saw it as a betrayal of their principles. But when Naismith was asked his opinion, he applauded Grange. Naismith said he saw nothing different between Grange turning pro and a coach getting paid to coach a college team.

Q5: I'm glad you brought up coaching. Naismith believed basketball was at its best when coaches were not involved in the game, only the players on the court. Might explain his lackluster coaching record at Kansas. [In retrospect, I’m ashamed at my potshot at Naismith. Oh well.]

Anyways, you've touched on this already, but how would you summarize Muscular Christianity's lasting influence on basketball and American sports? When you watch or read about sports, what jumps out at you as a legacy of the Muscular Christianity movement?

With basketball in particular, I’d say first and foremost that without muscular Christianity we don’t have the sport at all. It’s literally created at a muscular Christian institution and by a person who fits the muscular Christian mold. And it’s because YMCAs across the world championed the game that it gained a foothold.

Despite its origins, though, it’s interesting to me that basketball quickly moved beyond the mostly white Protestant world of muscular Christianity. Basketball proved to be an adaptable game that could be embraced by all sorts of communities—religious and otherwise.

You could write entire books (some already have) on the strong relationship between basketball and Catholics, Jews, or Mormons. We’ve already talked about how basketball was picked up by women. And then it became an important game for Black Americans, too, many of whom were Protestants, but who developed their own version of muscular Christianity that took into account the challenges and experiences of Black people living in a country dominated by whiteness.

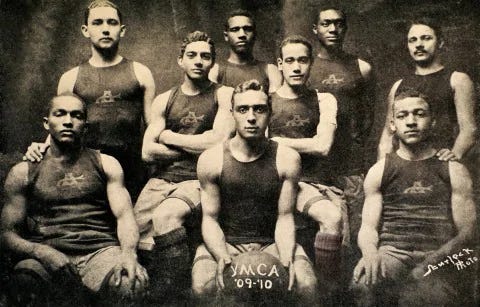

[ed. note: E.B. Henderson, holding the basketball, is often referred to as the father of black basketball. He protested the YMCA’s racial segregation in Washington, DC.]

There are a couple different ways to consider how those original muscular Christians might feel about all of this today. On the one hand, it’s reasonable to look at the white Protestant triumphalism of the movement and to say that muscular Christians might see basketball’s pluralistic and cosmopolitan development as a problem. They might lament the fact that basketball is no longer closely linked with the white Protestantism that helped to inspire its creation.

On the other hand, many muscular Christians of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries would have fit more into the liberal side of Christianity than the conservative side. They tended to be more open to change, less dogmatic, and to believe in progress, evolution, and social development. Some of those liberal Christians ended up taking the view that the principle or the value was the important thing, not the label—in other words, as long as basketball was able to contribute to human flourishing and positive character development, then it wouldn’t matter to them if the game was directly linked with a religious organization or a religious message. It was still doing God’s work.

That, I think, is where James Naismith would have landed.

In terms of muscular Christianity’s broad influence on American sports, one of the most important legacies is the idea that sports can be a site for moral formation. That notion is not exclusive to muscular Christians, of course, but they do a lot of work in popularizing it and making sure the idea continues even when the logic behind it (based on the purity of amateur sports) proves to be a farce.

And muscular Christianity also forged links between Christianity and sports that we still see today. Of course, those connections have changed considerably over the years. The YMCA, so central to the original muscular Christian movement, no longer works to spread Christianity. And these days conservative evangelicals, working through organizations like the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA) and Athletes in Action (AIA), tend to be the Christians most closely linked with sports. But even if there are some major differences, the newer crop of evangelical “muscular Christians” (if you want to call them that) often see themselves as part of the original muscular Christian legacy. Nation of Coaches, an evangelical sports ministry for college basketball coaches, has this for its mission statement: “to honor Coach Naismith’s spiritual design for the game, by empowering men’s college basketball coaches across the country to leave a legacy of excellence.”

Q6: Thanks for smartening everyone up. Now comes the time for the book plug! What's your upcoming book, The Spirit of the Game, about? And if it's not too sore a topic, when might we expect its release?

In many ways this interview is a great set-up for my book, because my book tells the story of American Protestant involvement in sports from the 1920s to the present—basically after the original muscular Christian movement. I picked the 1920s as the starting point because that is the decade when sports truly became a national obsession, when it became clear that sports at all levels could not escape commercialism. The original crop of muscular Christians, as we’ve discussed, thought that commercialism would take away the potential for moral formation through sports. Some of them stuck with that idea and grew disenchanted with the excess of sports in the 1920s. But some of them found ways to make peace with the money- and win-focused sports world that emerged. I tell the story of those sports-friendly Protestants, and I explain how they end up creating an entire subculture embedded within big-time sports where their Christian ideas and values can be promoted.

Basically, if you want to know how and why Christianity became a consistent and conspicuous presence in modern-day American sports, my book gives you the history.

I’m hoping I can finish it in time for a 2021 release date.

[Ed. note: Follow Paul on Twitter and BUY HIS BOOK WHEN IT COMES OUT]

Wilson Pickett singing “Rock of Ages.” The rock is a basketball. Or maybe Jesus. Either way, that man can sing.

Recommended Reads

If you can’t wait for Paul’s book, a good introduction to all of this subject matter is Clifford Putney’s Muscular Christianity.

And if you want a DEEEEP dive into this subject, check out Steven Overman’s The Prostestant Ethic and the Spirit of Sport.

SO. MUCH. AWESOME.