In history – both “normal” and basketball – it’s often easy to chalk up revolutions and seismic changes to great men (especially men) and dramatic moments. A heroic or cunning figure arrives on the scene works his magic and the world is forever changed because of his one-of-a-kind efforts. Or a phenomenal event shatters the world and people (usually the great men) are left to reassemble the wreckage into something new and altogether different.

Well, (basketball) history is more complicated than that.

For example, we have The Stretch Four. If you’re doing a Great Man History, perhaps Dirk Nowitzki is your standard bearer for The Stretch Fours. And not simply because he was excellent in the role, which he certainly was, but that he might mistakenly be considered the originator of the role itself.

Dirk came, he saw, he conquered, he dropped threes.

Of course, stepping back for a moment, there is the intrinsic problem of how did Dirk get his crazy Stretch Four idea? We all follow a path, no matter how raggedy, laid out by our predecessors. Perhaps we deviate or alter the path, but the existing trail was our guide.

Dirk didn’t magically Great Man into existence The Stretch Four. Which brings us to…

What makes Terry Mills such an interesting case in the evolution of The Stretch Four is that he did so as a mid-career shift.* In 1990, he didn’t enter the NBA from the University of Michigan as a three-point shooting specialist. The New York Daily News as late as August 1993 described Mills as a “6-9 low-post scoring threat” as they recapped his free agency bolt from the New Jersey Nets to the Detroit Pistons.[1]

*(Clifford Robinson and Sam Perkins were contemporaries of Mills in The Stretch Four movement and made similar transitions. Indeed many subsequent Stretch Fours did the stretch mid-career).

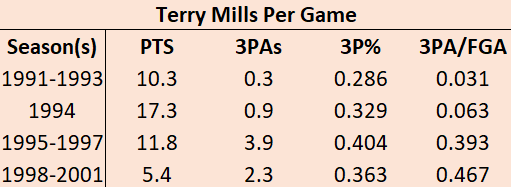

The 1993-94 season saw Mills produce his best raw scoring with 17.3 PPG. That season also saw Mills begin his transformation. For the first time, he notched a noticeable amount of three-point shots with 0.9 per game albeit on a mundane .329 clip. But clearly the bulk of his scoring still came via his post-up game.

For the 1994-95 season, Mills’s scoring average dipped from 17.3 to 15.5 thanks to the addition of rookie sensation Grant Hill. However, Terry’s three-point shooting jumped through the roof. He attempted a heroic 4.0 threes per game on a scintillating shooting percentage of .382.

For the 1995-96 season, Detroit dismissed coach Don Chaney who had unleashed Terry’s three-point shooting in favor of Doug Collins.

It’s dirty business changing the world. Not everyone appreciates the benefits of the change coming down the pike. And even those open to the positive possibilities are wary of the side effects.

We turn to the Detroit News for extended coverage of the perplexities:

Enigma. The word has haunted Mills since his prep days at Romulus.

He is 6-foot-10, 250 pounds and does few his size can. He scored 109 3-pointers last year, more than any other power forward or center, and dished out 160 assists. On the other hand, he often doesn’t do things guys his size should do: Be an intimidating presence inside and dominate the glass.

Even Collins has acknowledged this paradox.

“Big guys who can shoot live with the curse of people saying, ‘Well, there he goes floating to the outside.’ That might be his strength, but you want big guys arm-wrestling down in the post.”

Collins and the Detroit front office seemed to float toward the “arm-wrestling” side of things by adding more traditional big men - Theo Ratliff and Don Reid - in the draft, while also trading for veteran strongman Otis Thorpe in the 1995 offseason.

Back to the Detroit News:

Is it any wonder Mills is hearing mixed messages? Play your game, but give us a big presence. Mills is left nearly paralyzed by it all. Proof came Friday night. Several times he got the ball in spots along the perimeter. Before, he would shoot without hesitation. On Friday, he froze.

“I am just really confused right now,” Mills said. “All I read and hear about is how everybody wants me to shoot in the low post and post up. Then I get the ball on the wing and everybody in the arena knows I can make those shots, but I’m thinking, ‘Does he want to me to shoot this?’ Will I be a victim of shooting it, even if I make it? I just don’t have a grasp or a feel for what’s going on right now.

“The misconception is that I can’t play a low-post game. I can play inside or outside, either-or, just tell me which one.”[2]

Terry’s revolution wasn’t overthrown but it was curtailed somewhat. His playing time dipped drastically from 35 MPG in 1995 to 20 MPG in ‘96 before ticking back up to 25.5 MPG in ‘97.

But here’s where that perplexity shows up again.

Despite playing far fewer minutes because the Pistons wanted more muscle, when Mills was in the game he fired away from downtown at an even more prodigious and accurate clip.

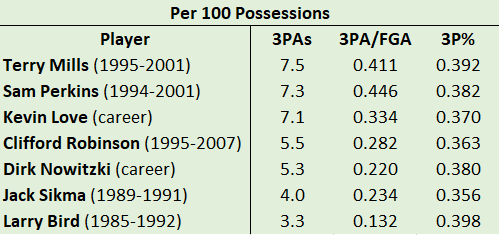

The difference starkly shows up when you check out the per 100 possessions numbers instead of the rawer per game numbers.

As you can see, not only was Mills escalating the attempts, his accuracy was rising simultaneously. Now some of this can be attributed to the shortened three-point line of 22’, which debuted in the 1994-95 season. However, Mills wasn’t just taking advantage of a rule change; he was actively improving his shot.

Trouble is, it gets kind of tricky proving Mills’s improved accuracy after the NBA returned the three-point line to 23’9” for the 1997-98 season.

Hitting the free agent market during the summer of 1997, Mills joined the Miami Heat, who certainly could have used his outside shooting next to Alonzo Mourning. Unfortunately, Mills struggled with knee injuries for the 1997-98 and 1998-99 seasons dramatically limiting his play and curtailing his effectiveness. After 50 games played in 1998, Mills played just one game in the 1999 season.

His three-point shooting was a miserable .318 those two years.

However, Mills triumphantly returned to Detroit for one more year in the 1999-00 season. He played all 82 games connecting on 39.3% of his 3.0 threes per game. Fully healthy, full three-point line and proof he had mastered the long-range bomb.

Mills’s final season was again injury-riddled as he suited up in just 14 games for the Indiana Pacers in the 2000-01.

So, in the end, Mills wasn’t an All-Star and often fluctuated between the bench and the starting lineup in his 11-season career. Yet, it’s players like him – those guys who unceremoniously clear a lot of the NBA underbrush – that clear up pathways for the dramatic changes in the game.

Superstars like Dirk Nowitzki (or Larry Bird for the older folks amongst you) can be designated as unicorns and given the leeway to play the game however they see fit. The Birds and Dirks can “indulge” in their three-point shots because they do so much else on the court.

The more “average” player like Mills who plays peculiarly is where the nitty gritty work of basketball revolution occurs. Mills certainly had other basketball skills, but being a Stretch Four was his most useful ability, if coaches weren’t afraid to let him play the role.

As Doug Collins and Mills admitted above, they were perplexed on how to make the best use of his skills. How do you juggle team dynamics, fan expectations, basketball culture and the individual’s psyche?

Pertaining to The Stretch Fours, the questions have been largely adjudicated over the last two decades. Teams are delighted to find a power forward able to bomb away from downtown.

And it’s folks like Terry Mills that laid the groundwork, even if they get overlooked in the longrun, which is of course why the ProHoopsHistory Newsletter exists. Someone’s gotta save these pioneers from obscurity.

[1] Howard Blatt, “Dudley a replay of Mills failure,” New York Daily News, August 4, 1993.

[2] Chris McCosky, “Solid stats, poor review for Mills,” Detroit News, October 15, 1995.

Image Credits

Rocky Widner / Getty Images

SkyBox Card from 1997-98 Season

Tables derived from data available at basketball-reference.com

TERRY MILLS LOVED THAT DOWNTOWN LIFE

Come for Hall & Oates doing a take on Minneapolis Funk. Stay for their underrated bass man, the mean T-Bone Wolk.

Unsolved ProHoopsMysteries

The idea of a “stretch 4” had to exist before the three-point line. So who were some of the first power forwards to roam the perimeter?

How many times will Otis Thorpe make a cameo appearance in this newsletter?

Who was a Stetch Four that shouldn’t have been trying to stretch things? That’s definitely a question to be answered soon…