Hank DeZonie: The NBA's Overlooked Barrier-Breaker

It’s hard to gauge current public knowledge of basketball’s racial politics in the 1940s and early 1950s. If only Quinnipiac did a poll. Alas.

What we do know is that the NBA enjoys a unique position in telling basketball’s history. And it does a relatively poor job on its own history as well as the story of how it came to exist.

So I would not be the least bit shocked if 99.99% of basketball fans are unaware that some pro basketball leagues before the NBA existed had porous racial boundaries. They weren’t necessarily integrated, but they weren’t exactly segregated either.

It was a hazy world of circumstantial integration. Normally white leagues would welcome in black players/teams when necessary to keep operations going. In addition there were the all-white barnstorming squads that typically felt no compunctions about playing black barnstormers. What happened off the court, particularly in the Midwest, was a different matter as these black teams were often turned away from many establishments because of racism.

Given this murky realm of race and basketball, it’s not shocking that the NBA, a fledgling league in 1950, also has a cloudy and uneven history when it comes to integration.

Perhaps the best way of revealing this truth is through the story of Hank DeZonie.

PIONEERS REMEMBERED

Hank DeZonie in the Rock Island Argus, December 1, 1950

Earl Lloyd. Chuck Cooper. Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton.

Those are the three men most often credited with breaking the NBA’s color barrier in 1950-51, the NBA’s second season. And indeed they did. All three players debuted within days of each other during the first week of that season.

However, several weeks later, another black player breached the NBA’s color line: Hank DeZonie. His brief five-game stint with the Tri-Cities Blackhawks draws little, if any attention, from most modern retrospectives of the NBA’s racial history.

The Undefeated recently ran an article discussing Converse’s special line of shoes honoring Lloyd, Cooper, and Clifton for Black History Month. Neither The Undefeated nor Converse are apparently aware of DeZonie’s contributions.

The NBA also seems unaware. Three years ago, the Atlanta Hawks - successors of the Blackhawks - produced a video with the wonderful Claude Johnson of the Black Fives Foundation discussing DeZonie. However, the league itself is blind on the matter. Straight from the NBA’s history website, there’s rightful discussion of Lloyd, Cooper, and Clifton, but nada on DeZonie…

To a degree, it’s understandable that Lloyd, Cooper, and Clifton garner more attention than DeZonie. After all they each played far more than five games in the NBA. However, DeZonie was an accomplished professional. Just because he didn’t last long in the nascent NBA didn’t mean he lacked basketball laurels. Indeed, several other great basketball players of the era never played a game in the NBA.

Furthermore, DeZonie’s cup of tea in the NBA helps give another very real angle on the process of integration: it’s messy, it’s uneven, it’s how history works.

Some trail blazers become an All-Star (Clifton), win an NBA title (Lloyd), or get inducted to the Hall of Fame (Lloyd, Clifton, and Cooper).

Others (DeZonie) get forgotten… so let’s remember.

RENAISSANCE MAN

DeZonie hailed from New York City and stood about six-and-a-half feet tall. The center’s professional career with the vaunted New York Renaissance in the 1943-44 season. This all-black barnstorming squad was the cream of the crop for professional basketball during the 1930s and was still a powerful force in the 1940s.

But DeZonie dabbled around the world of pro hoops.

As an institution, pro basketball, despite being five decades old in the 1940s, was still in a fairly fluid state. Players could ostensibly be “exclusive” to one team, yet clandestinely slip out for occasional games with other leagues or barnstormers. So, it’s unsurprising that DeZonie, ostensibly a Renaissance Man, was also poking his head around predominantly white leagues.

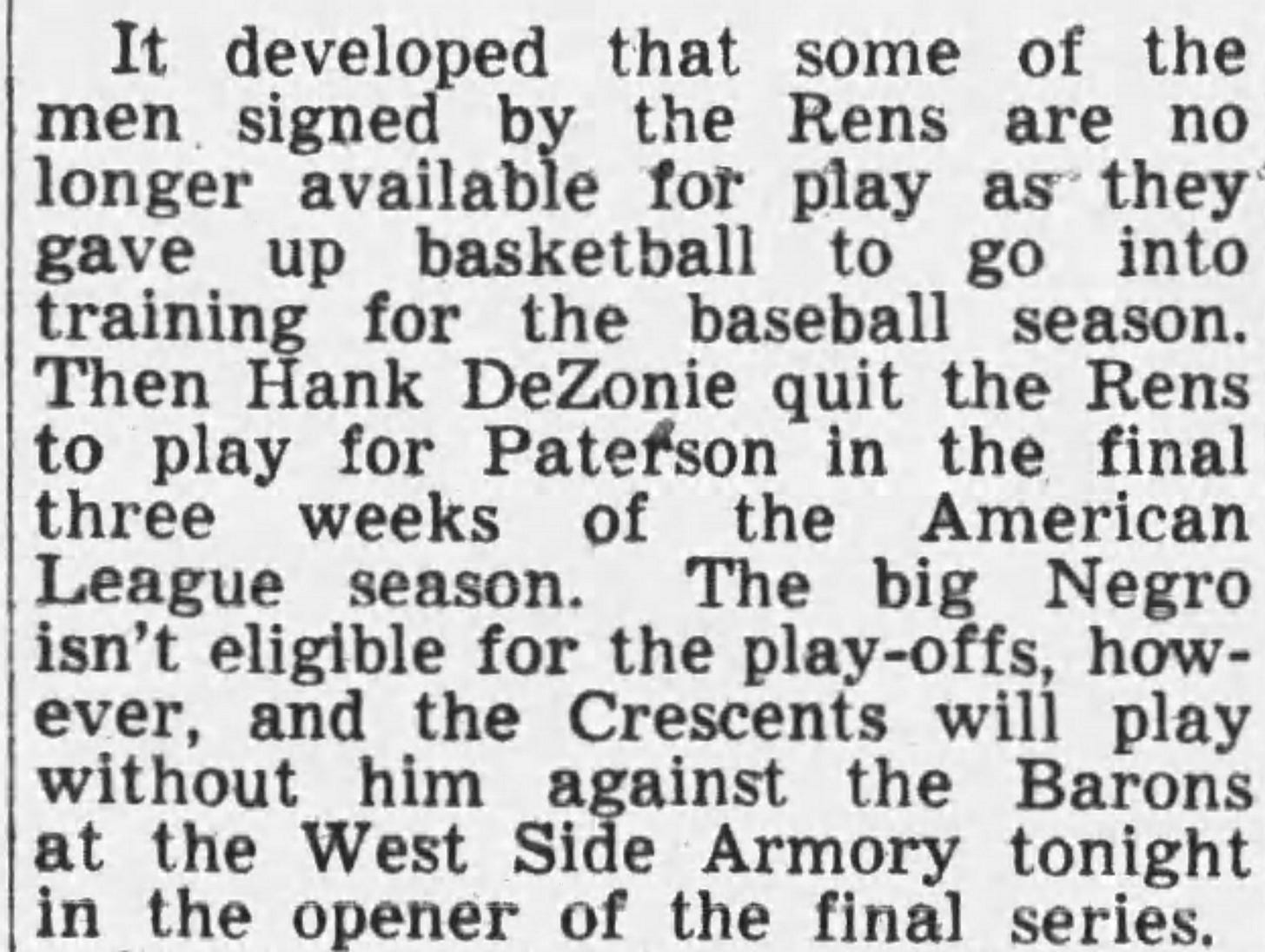

A report from the Wilkes-Barre Record on March 31, 1948, claimed that DeZonie had quit the Rens to play for the Paterson (NJ) Crescents of the American Basketball League (ABL):

More importantly, though, DeZonie and his New York Rens compatriots gave up the barnstorming life for the 1948-49 season and joined the National Basketball League (NBL). The NBL was one of those leagues that practiced that circumstantial integration. Beginning in 1942, the NBL employed black players, but not on a permanent basis.

By incorporating the Rens, however, the NBL now had an entire franchise completely composed of black players.

There was one BIG hitch to the Rens deal. The NBL was located primarily in the Midwest. The Syracuse Nationals were its easternmost club. So, the Harlem-based Rens were decamped to Dayton, Ohio, for the 1948-49 season.

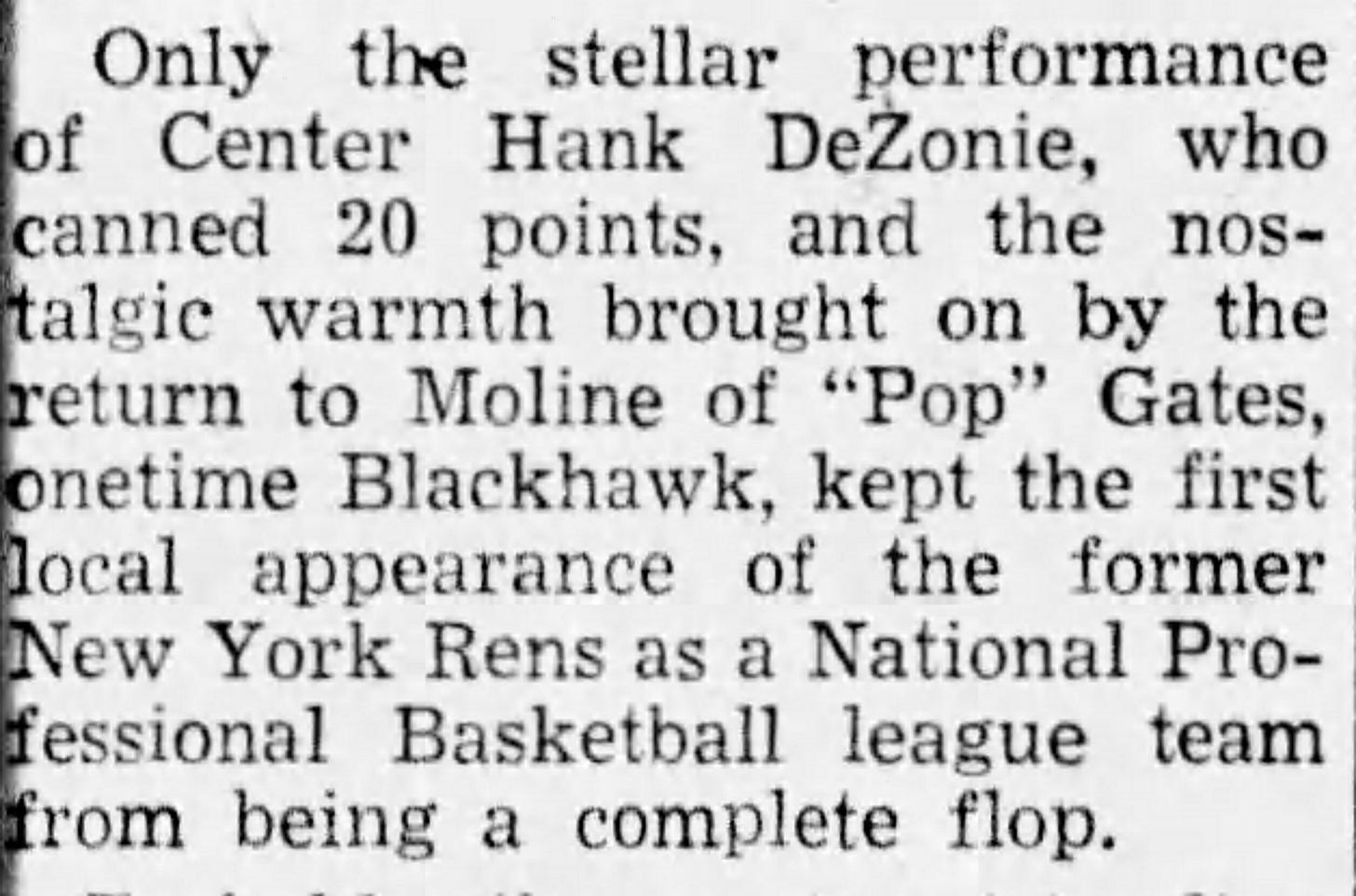

Things didn’t get off to a good start for the Rens. The Davenport Times on December 27, 1948, noted that the Tri-Cities Blackhawks drubbed the Rens, 70-49. The paper gave special notice, though, to DeZonie as well as William “Pop” Gates.

(Notice the paper mentioning that Pop Gates was once a Blackhawk. Otherwise all-white, the Blackhawks employed Gates the previous season thus briefly integrating their team. Circumstantial integration in action.)

DeZonie’s wandering ways meant he only appeared in 18 of the Rens’ 40 NBL games. During that time he led the team in PPG with a 12.4 average. Overall, the excellent Gates led the Rens with 11.2 PPG and a total of 448 points.

By March 1949, DeZonie was again playing for another team: the Harlem Yankees. In an exhibition game chronicled by the Wilkes-Barre Record on March 24, 1949, the all-black Yankees played the Wilkes-Barre Barons of the ABL, who drubbed them 100-68.

As for DeZonie’s old standby, the Rens, they unfortunately went asunder. Under financial stress, the club was sold to the rival Harlem Globetrotters. Most Rens players, however, refused to report to the Trotters claiming they had not been fully paid for their work in the 1948-49 season.

DeZonie was one of those players asserting his agency and continued playing for the Yankees, who became members of the ABL for the 1949-50 season. This meant that yet another all-black team had joined a predominantly white league - all while the NBA, formed in 1949, maintained a strictly white league.

DeZonie would spend most of the rest of his professional basketball career, which lasted at least through 1952-53, with the Yankees. According to the Pro Basketball Encyclopedia, DeZonie accumulated more points in the ABL from 1949 to 1953 than any other player in the league.

That fact makes it all the more curious that DeZonie had such a short stint in the NBA when he clearly had the talent for at least one season of play.

Help this newsletter last more than one season.

TO THE NBA

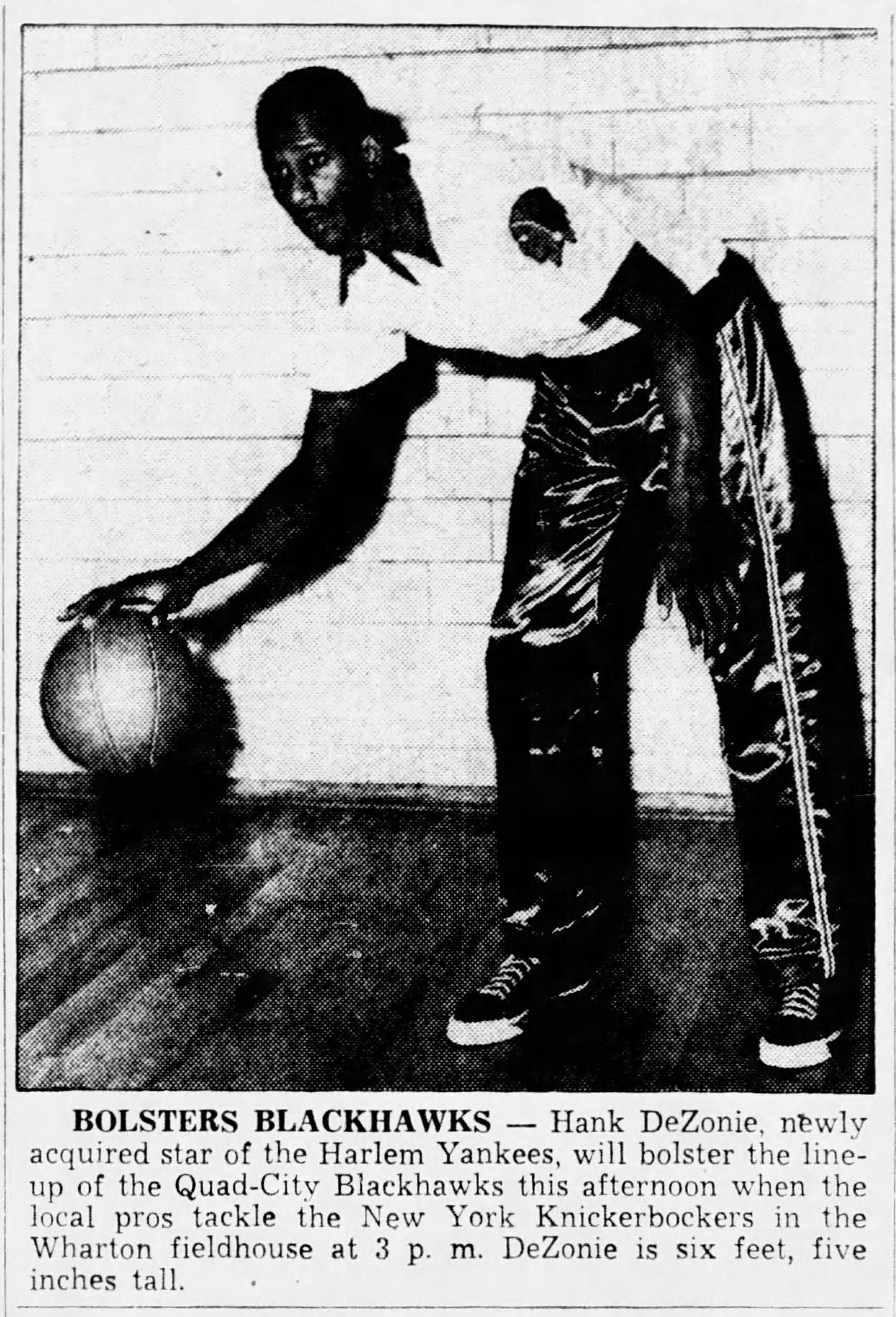

Quad-City Times, December 3, 1950

In December 1950 - a month after Lloyd, Clifton, and Cooper had made their debuts - the Tri-Cities Blackhawks came calling for DeZonie.

(The Blackhawks became an inaugural member of the NBA in the 1949-50 season when the NBL merged with Basketball Association of America [BAA] creating the NBA. And remember the Blackhawks had employed a black player [Pop Gates] while members of the NBL, so while the NBA was being integrated, one of its franchises was just re-treading the same old ground.)

On the surface, DeZonie’s five-game stint with the Blackhawks was less than impressive. Perhaps the travel from New York out to the Tri-Cites of Iowa/Illinois threw DeZonie off. He averaged a mere 3.4 points per game and the most notable action I could find of DeZonie was a recap of a game versus the Fort Wayne Pistons on December 7, 1950.

The game garnered special notice from the local Tri-Cities press because the Blackhawks blew a 17-point lead. With just three seconds remaining and the score tied at 76, DeZonie took a corner shot for the win. It missed and his teammate Dike Eddleman was called for a loose ball on the rebound attempt. The Pistons made a free throw and took the game before a distraught crowd in Moline, Illinois.

DeZonie’s NBA career didn’t last much longer. A week later on December 13, the Quad-City Times carried a notice that DeZonie had been waived by the Blackhawks.

Big Hank rejoined the Yankees in the ABL and continued with his pro career, the NBA portion largely forgotten.

So why did DeZonie last just five games?

Well, for starters the Blackhawks were a bit of a mess. Just a day or so after DeZonie was put on waivers, head coach Dave McMillan was fired. For the rest of the season John Logan (3 games) and Mike Todorovich (52 games) served as player-coach. Team owner Ben Kerner would become notorious for endlessly hiring and firing coaches and being particularly fond of the player-coach model.

Guess it helped with the finances to pay a man to do two jobs.

But that nonsense aside, it seems that life on the Great Plains wasn’t DeZonie’s style. In an interview with Peter Vescey in 2004, DeZonie explained:

“I was staying in some old rooming house run by some old woman and the coach didn’t know night from day. I lived better than that. Once the days in the bus were over, it was more fun playing in the schoolyard.”

With that, DeZonie headed back east to the Harlem Yankees and the ABL.

So, what to make of Hank DeZonie?

He played a mere five games in the NBA, but that was because as a veteran of pro basketball he wasn’t putting up with any belittling treatment. Furthermore, the ABL centered on New York State and Pennsylvania thus providing him easy travel from his home in New York City. Why put up with poor accommodations in someplace you’re not used to (Moline, IL) when you can live comfortably in your home (New York) and make comparable money?

I guess what we can make of DeZonie is that to fully understand the racial integration of the NBA and professional basketball, we have to dig into all the ways it happened. No matter how brief or seemingly trivial the happenings were

Lloyd, Cooper, and Clifton enjoyed lengthy NBA careers and tell their own particulars on how race played out in the 1950s NBA.

So too does DeZonie.

TEAR DOWN THESE WALLS

Gotta enjoy a Teddy Riley produced New Jack Swing song employing Ronald Reagan foreign policy speeches.