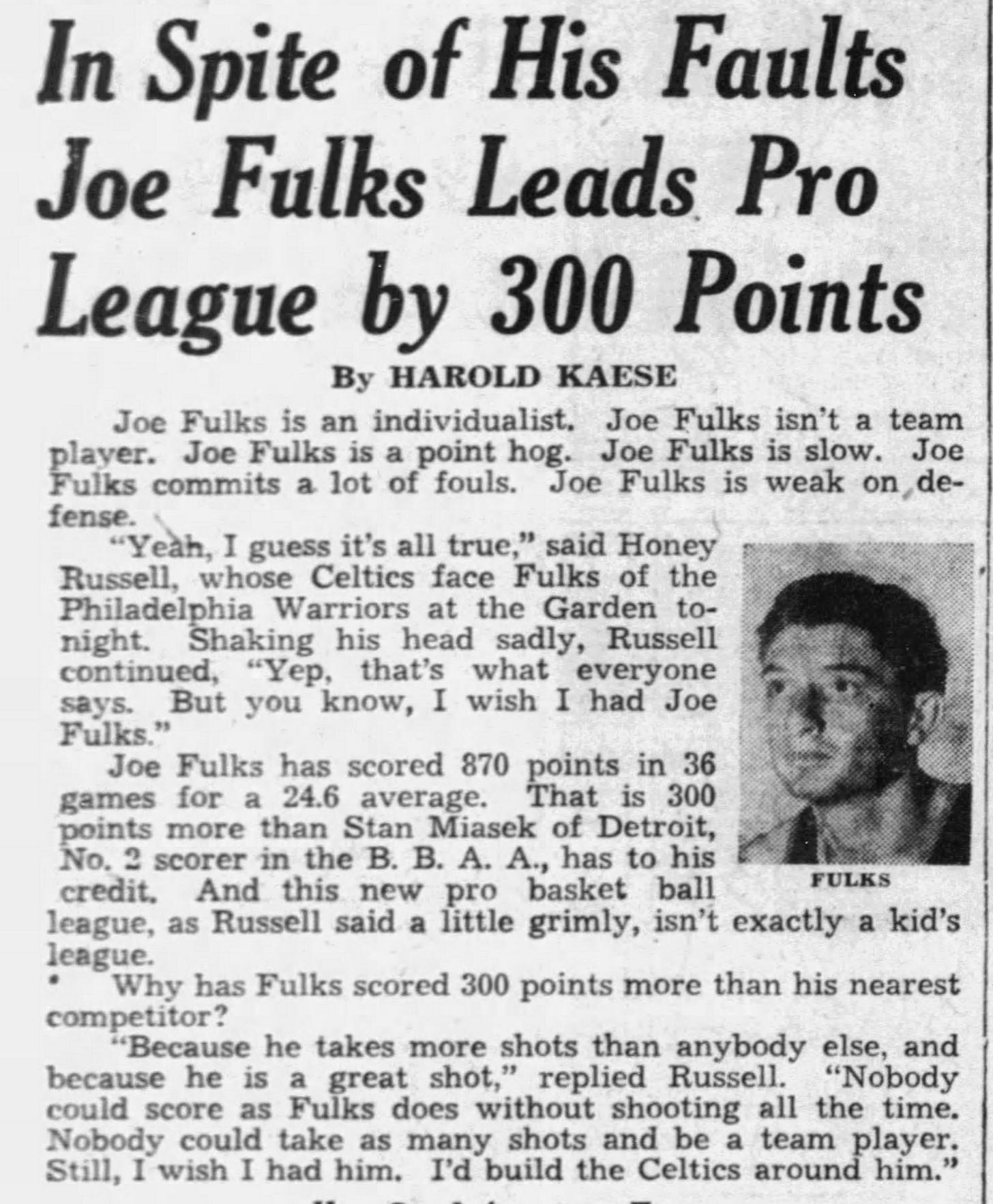

Typically, it’s not good form to open an article with a lengthy citation of another article, but hot damn, this story from the Boston Globe in 1947 perfectly captures the essence of Joe Fulks.

This assessment of Mr. Fulks holds up nearly 75 years later. Did he shoot too much? Probably. Did he pass often? Nope. Would you still want him on your team? Yeah.

It seems somewhat absurd you’d want a shoot-first, pass-never forward, but the decades of time have dulled the excitement and transformative play of Fulks.

Make no mistake, this man was a revolutionary. The way he played was instrumental in not only progressing the game of basketball, but in keeping the Basketball Association of America (BAA) afloat long enough to become one of the two leagues that the National Basketball Association now rests upon.

“Jumpin’ Joe” didn’t earn that bouncy nickname for stupendous dunks. To be honest, he didn’t even jump that high. Instead the need for a marketable moniker was because Fulks practically knew no restrictions on what shots he would take and make.

Growing up in Kentucky, Fulks would spend his days (and nights) practicing on a hoop outside the local school. He started out shooting tin cans and old beat up basketballs. John Christgau in his awesome book The Origins of the Jump Shot described Fulks’s basketball growth as a child during the Great Depression in 1932:

One day halfway through that season, Joe Fulks and James Defew stood with their friends at courtside and watched Robert Goheen score repeatedly with an exciting, two-handed leaping shot. For boys who had not yet even mastered the skill of bouncing the ball, the mechanics of leaping to shoot might have seemed too difficult to learn just then….

Hour after hour [Fulks] practiced a wide assortment of creative shots that went beyond what Sanders had taught him. Baby hook shots, running or standing, shooting from his chest, or off the shoulder with his body turned, or whirling and stepping or just standing….

Finally in 1936, Goheen, the local basketball star who had now returned home, told Fulks how to use his legs to propel the shot instead of using only his arms. Fulks still didn’t jump high on his shots—could barely clear a piece of paper—but he used his legs. And he also could use either hand. The old habit of slinging from his shoulder persisted somewhat, so Joe would go into a shooting motion sometimes without knowing which hand he’d shoot the ball with, only deciding after perceiving which shoulder a defender was leaning towards.

The unorthodox play made Fulks a highly-sought college recruit thanks to an excellent high-school basketball career, Fulks chose to attend Murray State before joining the Marines during World War II. In 1946, Fulks became a 25-year-old rookie in the BAA after signing a whopping $8000 contract with the Philadelphia Warriors.

With that sort of wild, unorthodox basketball upbringing, you can see why Joe would have no hindrances when it came to taking outlandish running one-hand push shots, or running hooks, or even the occasional jump shot in the pros. But note that he was taking running shots. That’s what really set him apart from his contemporaries. The willingness to shot on-the-go instead of getting his feet nice and set.

Some demeaned Fulks’s shooting as showboating, but ya can’t argue with results. He led the BAA in scoring with 23.2 points per game in the 1946-47 season. (Second-place finisher Bob Feerick averaged just 16.8 PPG.) And that’s 23 PPG for an individual at a time when teams averaged 67 PPG as a whole.

Fulks’s Warriors finished 35-25 and wound up capturing the BAA’s first title in five games over the Chicago Stags. In Game 1 of that series, Fulks was firing on all cylinders according to the Toledo Blade’s account on April 17, 1947:

The Chicago Stags, ordinarily no pushovers, were suffering today from a bad case of Joe Fulks jitters, an ailment common to teams in the Basketball Association of America.

Fulks, a skinny Kentuckian with the shooting eye of a well-drilled Blue Grass feudist, scored 37 points last night as his Philadelphia Warriors defeated the Stags, 84 to 71, in the first of a seven-game series for the league championship.

Chicago was only six points behind at the end of the third period, after which Fulks settled down to do some serious scoring. He sank eight field goals in nine tries and five out of five free throws for 21 points in the final quarter.

In the close-out Game 5, Fulks had a handsome 34 points to eke out an 83 – 80 victory.

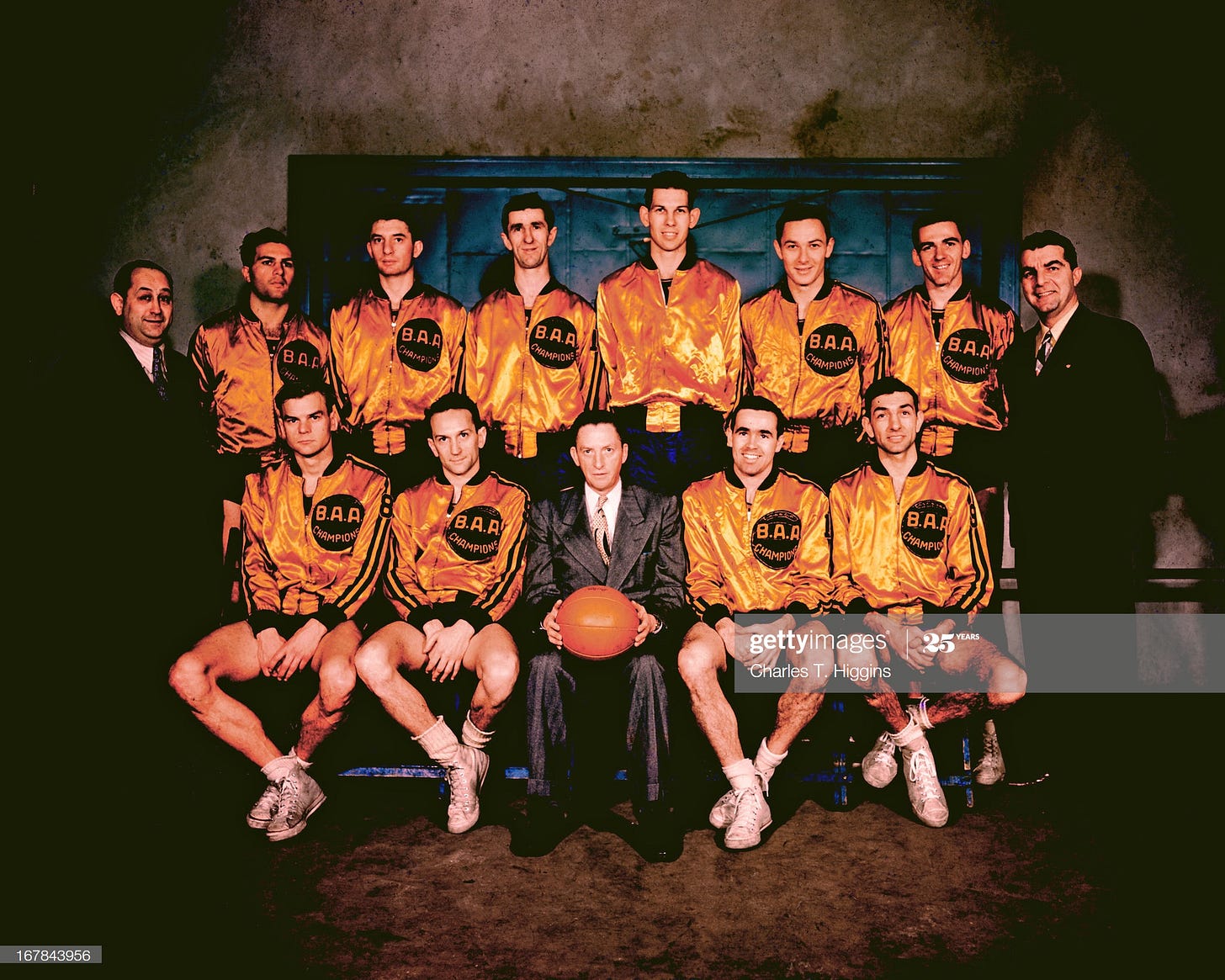

The 1946-47 BAA Champion Warriors

For an encore in the 1947-48 season, Fulks again led BAA in points (22 per game) and again led the Warriors to the BAA Finals. This time, however, they were defeated by the Baltimore Bullets in six games.

In the 1948-49 season, the BAA raided the National Basketball League (NBL) and acquired the Fort Wayne Pistons, the Indianapolis Kautskys (rechristened the Jets), the Rochester Royals, and the Minneapolis Lakers franchises. This meant that the NBL’s great scoring machine, George Mikan, could now go toe-to-toe with the BAA’s “Kuttawa Clipper”—personally I think that nickname is much better for Fulks since he went to Kuttawa High School.

Well, Mikan won the season scoring title with 28.3 PPG compared to Fulks’s 26. But that didn’t mean it wasn’t exciting for basketball fans at the time to follow the action as the giant Mikan with his sweeping hooks was juxtaposed to the more varied scoring attack of Fulks.

For example, Fulks downed the Indianapolis Jets with a stunning one-game mark of 63 points, the most by a player in either the BAA or NBL to that point. Indeed, no NBA player would exceed it until Elgin Baylor in November 1959:

Joe’s 63 points cracked the league record of 48 established by Minneapolis’ George Mikan Jan. 30 against Washington. His 27 field goals also was nine better than the league record he held jointly with Mikan and Carl Braun of the New York Knickerbockers.

Fulks told the Associated Press, “I knew I was hitting good and that something was going on by the way the crowd kept yelling ‘shoot, shoot.’” The dazzling forward continued, “But, honest, I didn’t realize I had a record until Eddie [Gottlieb] called me over and said to hang back. He told me then I had 59 points.”

And here I think we should get a li’l more context for the scoring exploits.

Fulks’s 63 points came in the pre-shot-clock era and the final score of the game was 108-87 in favor of the Warriors. And Fulks shot a ridiculous 27-56 from the field. (You’ll understand by article’s end why that was so ridiculous.) Baylor’s 64-point outburst on November 8, 1959, was a 136-115 victory for his MPLS Lakers over the Boston Celtics. Elgin shot 25-47 from the field. His scoring came after the shot clock, hence the higher game score.

This isn’t besmirching Baylor, but just to emphasize how silly it was for someone to notch 50+, let alone 60+, points before the shot clock. Anyways, that innovation was still a few years off.

In fact Fulks never did play under the shot clock regime.

However, he did play in the new NBA which started in August 1949 when the NBL and BAA ended their war and merged. In their final BAA season, the Warriors had slipped to an average 28-32 record. But in the first NBA season they collapsed to just 26 wins with 42 losses. Mirroring the slide, Fulks’s scoring drooped from that miraculous 26 PPG in 1949 to just 14.2 PPG in 1950.

Sure, the consolidation of pro basketball had something to do with it. Generally tougher opponents and perhaps players getting wise to Fulks. But Mikan’s average basically held steady with 27.4 PPG in 1950, which was only a slight dip from his 28.3 PPG in 1949.

Well, age was certainly a factor for Fulks, but more importantly alcoholism began to take its toll. He missed all but two minutes of the 1949 BAA playoffs because he injured his hip in a fall down the cellar steps in his home. Fulks didn’t tell Warriors management about the fall until 24 hours had passed. One can only speculate what inebriated condition he might have been in prior to falling down the stairs and hurting his hips. The Philadelphia Inquirer noted on March 24, 1949, that “Although his hip was cut and badly bruised, Joe attempted to treat it himself with a heat lamp, a course which nullified any possible chance of getting him ready to play.”

Thanks to the hip, and being 28 years old, “Jumpin’ Joe” no longer glided as well he used to as he found a growing fondness for the bottle. For the last five years of his career he’d average just 12.5 points per game after a 23.9 average over his first three seasons.

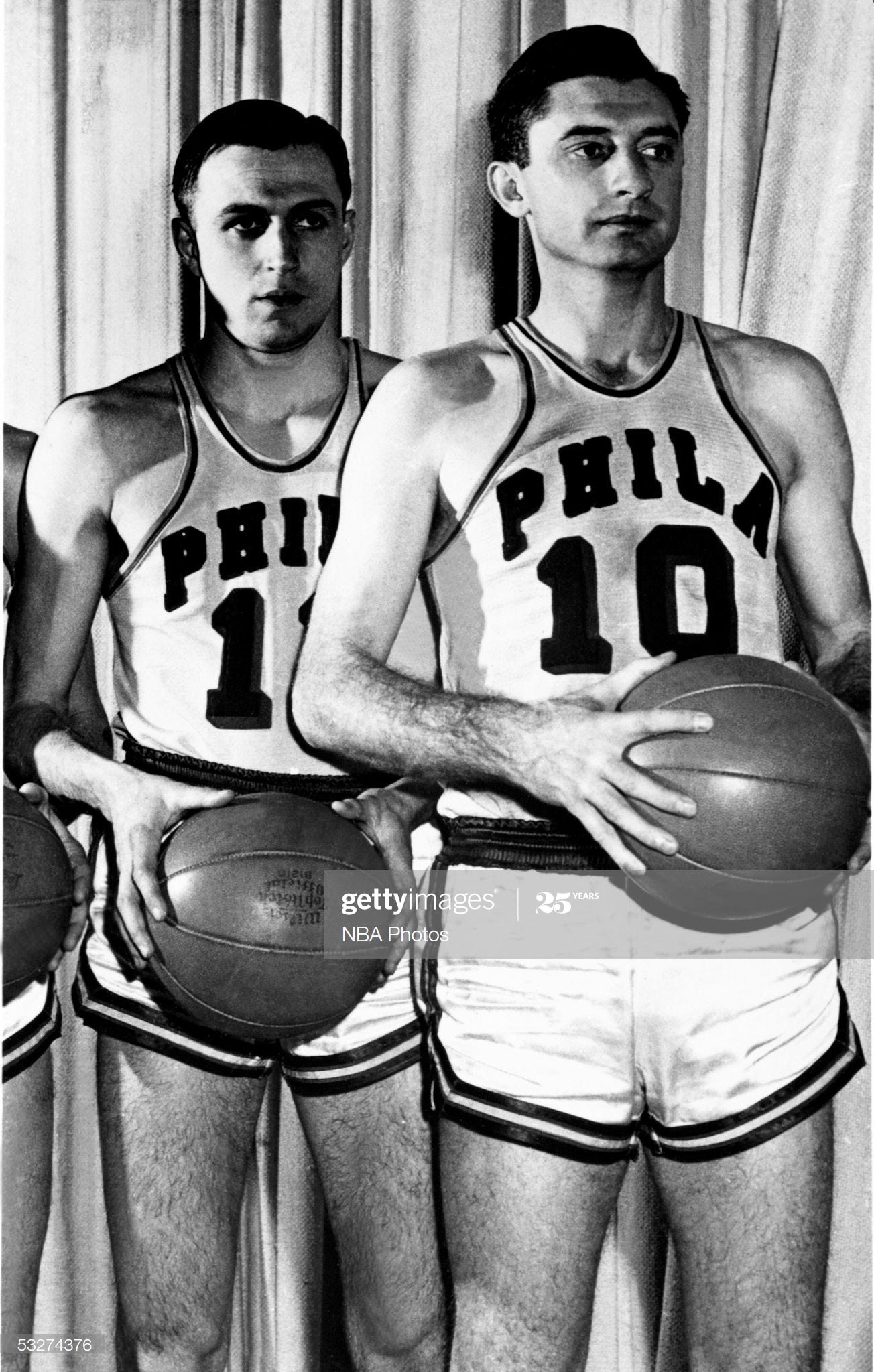

Fulks (#10) with his Warriors understudy Paul Arizin

In 1951, aided by the arrival of rookie Paul Arizin and veteran point guard Andy Phillip, Fulks put together a renaissance season where he averaged 19 PPG and eight RPG while leading the NBA in free throw percentage with a .855 clip. He was selected to play in the very first NBA All-Star Game that season as well.

The Warriors posted a 40-26 record and this was probably the best all-around team that Fulks ever played for. Perhaps the team that won the BAA title in 1947 was better because Fulks was bottled lightning that year, but the 1951 team was indeed more of a team. Alas, they were upset in the playoffs by the Syracuse Nationals despite Fulks continuing his renaissance with 26 PPG in the series.

The 30-year-old Fulks appeared in the 1952 All-Star Game averaging a respectable 15 PPG that season as Arizin really took hold as the team’s leading man with 25.4 PPG. However, Arizin was lost to the Marine Corps draft in 1953 and 1954, but another super scorer in center Neil Johnston rose to take his place those years averaging 23.4 PPG.

But the team stunk.

In 1952, they had a 33-33 record thanks to Arizin’s monstrous year. But in 1953, they were terrible with a 12-57 record. Things were merely bad in 1954 with a 29-43 record. For Fulks, 1954 was his worst and final season. Just 2.5 PPG for the former superstar.

The bottle ultimately ended Joe’s life in 1976. Residing in Kentucky once again, Fulks got into a drunken argument with his then-girlfriend’s adult son. The younger man eventually grabbed a shotgun and shot Jumpin’ Joe, instantly ending his life at age 54.

The man who had practically been the only gate attraction for the fledgling BAA in 1946 and ‘47 garners little attention, to say nothing of appreciation, these days. At least George Mikan has seven pro championships, so he can’t possibly be ignored, even if he too ultimately goes underappreciated. Fulks has “only” one title to his name. Easy to skip over and move along.

And to make matters worse there’s his shooting percentage—the elephant in the room when discussing his legacy.

Remember when I mentioned his shooting performance in the 63-point game was astounding? 56 shots from Fulks wasn’t shocking (okay it was a little). That he made 27 of them is remarkable.

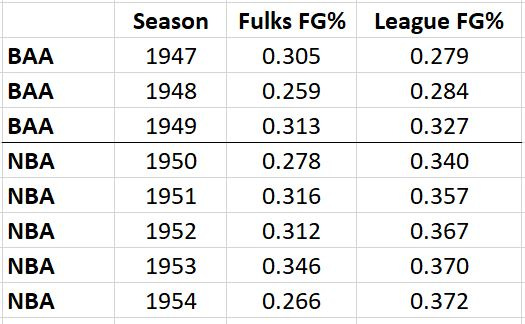

Modern analysts or enthusiasts with no historical perspective can point to his woeful career field goal percentage of 30% and call it horrendous, which it certainly is even by 1960s standards. But it wasn’t 2020 and not even 1960 yet. So let’s grab some historical perspective. In 1947 the average FG% in the BAA was 28%. By 1953, the NBA’s FG% was a more respectable 37%, which is still abysmal by today’s standards.

In truth, Fulks’s FG% meandered from about average to below-average for his era, but how he took his shots is what makes him extraordinary.

As a stringy forward who loved to swing long-range hook shots, one-handers, contorting jumpers, and all kinds of shots believed to be uncalled for, Fulks should be lauded as a herald and maker of the future. Maybe you didn’t want to shoot Joe’s percentage, but you certainly wanted to shoot like Joe.

It’s alright, though. Fulks took the lumps of being “the first” to play this way, so that others like Arizin and Baylor could come in later to perfect what Fulks dreamed up while adding their new additions to the stylistic tale.

Came for the news clipping, stayed for the article.