Juneteenth

The Process of Emancipation

In the wake of mass protests and civil unrest over police brutality and racism, America’s corporations were quick to declare after several hundred years that “Black Lives Matter.” I mean if Papa John’s tweets about it, then we’re well on our way to solving racism!

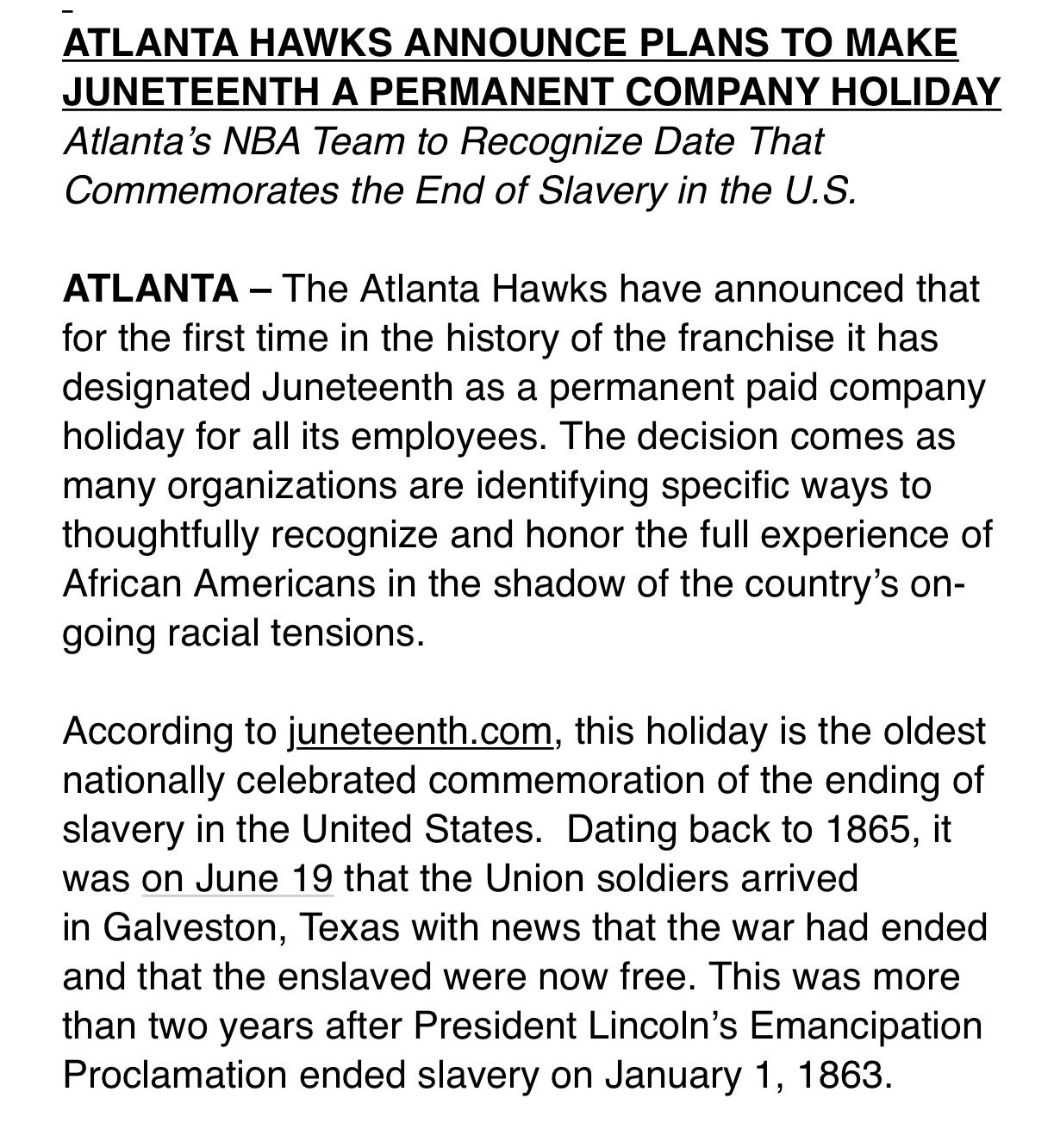

That initial spate of tweets that shook white supremacy to its to core was then followed up by corporations falling all over themselves concerning Juneteenth. NBA teams included. Trouble is they only have the faintest idea of what exactly they’re falling over.

At this point every NBA team has put out tweets concerning Juneteenth and now that everyone has got that out their systems, it’s time to get some education. Don’t want to be here this time next year with teams still putting out hokey Juneteenth messages.

After all, closing an office doesn’t automatically signify you understand the significance of Juneteenth. Or the process behind emancipation generally. For example, the NBA tweeted out this historically inaccurate statement…

Juneteenth isn’t the oldest emancipation day. It’s not a national emancipation day. There are several emancipation days in the United States that are older. And settling on a national emancipation day is a thorny proposition given how piecemeal emancipation was in the U.S.

Basically, it’s cool if we want to have Juneteenth stand in as the day to commemorate emancipation, but it is not the day that emancipation happened in the United States.

Let’s buckle up for some history…

GALVESTON, TEXAS — 1865

I grew up in Galveston County. Not the city of Galveston itself, but in the county. I’m a seventh-generation Texan and Juneteenth is a big deal back home. My people didn’t start off in Galveston County. They were born in places like Mississippi, Georgia, Virginia, and Florida. But throughout the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s Texas was held up as a paradise for slavery. “Virgin soil” to plant cotton and make a fortune. So my enslaved ancestors, like thousands of others, were dragged hundreds upon hundreds of miles to Texas.

For the most part, my ancestors toiled in the central part of the state, far from the coast.

On June 18, 1865, the United States began reasserting control over the renegade state of Texas after four years of civil war. As the largest city and busiest port in the state at the time, Galveston was a natural starting point for the military and federal authorities to accomplish this task.

The next day, June 19, United States Major General Gordon Granger stepped out on the balcony of the Ashton Villa, a home that previously served as HQ for the rebel army in the region, and read General Orders No. 3:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Essentially, this was Major General Granger informing Texas of the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order drafted by Abraham Lincoln during the summer of 1862 and signed into action on January 1, 1863.

This freedom didn’t immediately spread from Galveston to the central Texas, but I’m sure people were ecstatic they could finally relieve themselves of the shackles…

Word of the Juneteenth order was new news, but the Emancipation Proclamation was not. Perhaps not every enslaved person in Texas knew about it, but after 2.5 years, it certainly was generally known across Texas and the whole country.

It certainly caused a stir among the rebellious Confederates, who used it as proof that their treacherous gambit was a stroke of genius to evade the nefarious anti-slavery advocates and abolitionists of the Republican Party. Here’s Jefferson Davis on January 12, 1863, laying out the dramatic stakes that had been raised by Lincoln’s Proclamation of January 1, 1863:

[T]he proclamation… has established a state of things which can lead to but one of three possible consequences: the extermination of the slaves, the exile of the whole white population from the Confederacy, or absolute and total separation of these states from the United States.

Word of the Proclamation naturally fanned out across the South to Whites and Blacks alike. The United States Army and Navy, as they defeated the rebels and pressed along the Mississippi and Red Rivers, liberated enslaved people and spread pocket-sized copies of the emancipation order fairly close to Texas. The contraband info, if not the booklets themselves, certainly penetrated the border and into the minds and consciousness of Black Texans.

On the flip side, enslaved Southerners had been flooding U.S. military lines since 1861. Their attempts and success at freeing themselves had pressed the federal government to act faster and more radically on emancipation than had been contemplated when the war began.

Lincoln himself told some upset White Kentuckians, “I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.” The events were the awesome scale of the war and the unrelenting demands and actions for freedom by Black Americans.

The North Star for Black freedom during the war was the U.S. military. It was an illuminating force magnetically attracting Black Southerners away from their work camps. Doesn’t mean the White officers and soldiers were always happy to see Black people showing up uninvited, but it kept happening and happening. Wherever the U.S. military went, Black people slipped away from farms and cities to join up.

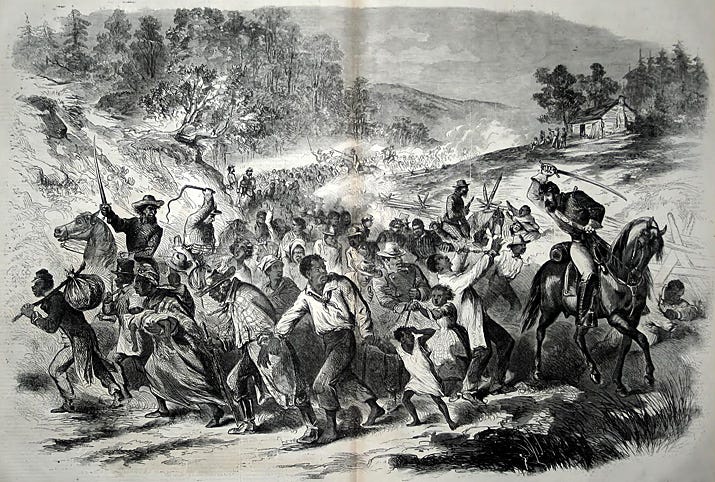

And this was absolutely noticed by White Southerners. Desperate to cling on to their chattel property, angry Whites drove thousands of enslaved people on forced marches to evade the magnetic U.S. Army.

Harper’s Weekly illustration of the forced marches from 1862

The safest place for slavery—because it was so far away from most of the war’s action—was Texas. Historian Andrew Ward in his book The Slaves’ War compiled recollections that Black Southerners had on the experience. Here’s but one remembrance from a former slave, Jake Wilson:

That was sure some trip when us come to Texas. Old Master had done been to Texas and traveled round through the state looking for a place to locate. [He purchased] 320 acres of land at what they call Whitehall [near Waco]. There weren’t no roads much, nor no bridges in Texas…. It took us about three months to get to the place in McLennan County where us going to locate.

These forced marches proved that slave masters were not too keen on just giving up their property. It’s one thing to sign or read an emancipation order. It’s quite another to fan out across the giant state of Texas—let alone the whole South—and enforce the order.

People in Galveston might have gotten freedom that first Juneteenth, but Jake Wilson out near Waco or my ancestors near San Antonio might have waited a few days or even weeks until U.S. soldiers showed up to make sure the enslavers gave up their barbaric jig.

And that leads to the perplexing nature of Juneteenth and the process of emancipation in the United States. No one single day suffices as THE end of slavery in the country. There was no magic moment anywhere where the institution just suddenly died.

It took consistent, hard work to bring about its end from enslaved people and an increasingly large alliance of others that culminated with the United States Army bringing the force of military arms to bear in the struggle. Which brings us back to the order that Juneteenth springs from…

EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION—1863

This might be the most confusing document in American history with accusations that it did too little (or even nothing) to wildly oversold praise that it was the cure all.

Look no further than the Atlanta Hawks’ slapdash press release:

“According to juneteenth.com…” for the love of God, consult a historian.

Anyways, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery on January 1, 1863. Practically, legally, or otherwise. Nor was it an empty gesture.

The Proclamation declared:

[A]ll persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

Essentially, all enslaved people within the rebellious states—with the exceptions of Tennessee, parts of Virginia (most of which became West Virginia a few months later), and southeast Louisiana—were considered free by the United States’ federal government. And that freedom would be “maintained” by the U.S. military.

As if the threat of federally-sanctioned emancipation wasn’t bad enough, Lincoln truly horrified the master class of the slave states (and a sizeable portion of the White North who wanted the Union “as it was” with slavery intact) when he opened up the U.S. Army to Black recruits. Ole Abe went a step further when he “hereby enjoin[ed] upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence[.]”

Soak that in for a moment. This is the first time in American history the president told Black people, “Hey, y’all got the right to use violence against White people.”

(Obviously Black people had used violence to resist slavery before ranging from broad rebellions in New York, South Carolina, and Louisiana to moments of personal resistance such as Frederick Douglass whooping his overseer’s ass to Margaret Garner killing her own child rather than seeing her offspring re-enslaved.)

So that’s the radicalism of the Proclamation, but it wasn’t the full demolition of slavery. It had its restraints.

As I mentioned, Tennessee, what became West Virginia, and southeast Louisiana were exempt. As were the “Border States” of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. Those four states had slavery, but remained (mostly) loyal to the United States in the war. By Lincoln’s estimation he had the legal authority to strip rebels of their so-called property, but loyal citizens.

Furthermore, signing a piece of paper in the White House—as Lincoln did—did not mean the immediate end of slavery even in the areas he targeted. Remember, it took 2.5 years for the military to show up in Galveston to make Juneteenth happen there.

A similar story played out across the South, just on different timelines.

Ulysses Grant’s campaigns near Vicksburg in 1862-63 and in Virginia in 1864-65 were their own constant “Juneteenths.” William Sherman’s campaigns in Georgia (1864) and the Carolinas (1865) were also “Juneteenths.” Less famed assaults by the army and navy in Jacksonville, northern Alabama, Arkansas, the coastal Carolinas, and so on did the work of nibbling away at slavery.

Especially in 1864 and 1865, many of these military assaults on slavery were led by United States Colored Troops.

Slavery in the “Border States” and exempted states began looking like Swiss cheese as people slipped out of bondage to either join the U.S. Army or disappear in big cities like Baltimore. These are yet more emancipation days happening in a rolling, ongoing personal fashion.

One such personal emancipation day we’ll check out is Louis Hughes from Tennessee.

Louis Hughes at age 65 in 1897

In 1862, before the Emancipation Proclamation and after his fourth failed attempt at escape, Hughes recalled in his autobiography that the plantation mistress accosted Hughes and his wife for the insolence of seeking freedom. For their sins of desiring freedom they would never see God, she declared.

Finally in July 1865—after the first official Juneteenth in Texas and after the state of Tennessee had ostensibly abolished slavery—Hughes and his wife, Matilda, escaped the plantation and arrived in Memphis. “It was appropriately the 4th of July when we arrived,” Hughes wrote. “Thousands of others, in search of the freedom of which they had so long dreamed, flocked into the city of refuge, some having walked hundreds of miles.”

Lincoln was assassinated by that point, Juneteenth had occurred, and yet the work of emancipation was still ongoing. Slavery was still legal in Kentucky and Delaware. Recalcitrant of White folks in many states defied the law and refused to let their “property” go.

The legal end of chattel slavery wouldn’t be complete until December 1865 when the 13th Amendment was ratified to the U.S. Constitution… and even then there was the outlier of Indian Territory to deal with via treaties concluded in 1866.

Anyhoo, the 13th Amendment read simply, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” This amendment was necessary forestall any re-implementation of chattel slavery.

Now that amendment wasn’t perfect. Notice that bold part. That’s what allows for convict labor. However, it was still supremely welcomed and necessary.

Lincoln believed that his proclamation only stood legal muster because the country was amidst a civil insurrection. And since that insurrection stood upon the institution of slavery, it was necessary to root out that institution to suppress the rebellion.

However, what might happen in Texas, say, in 1875? If there’s no longer an insurrection, the president’s executive order is no longer applicable. Perhaps Texas decides to re-enslave its Black population.

Even with the 13th Amendment, we got sharecropping. Even with the 15th Amendment, Black men (and eventually Black women with the 19th Amendment) were essentially denied the right to vote from the 1890s to the 1960s, so that’s not a crazy thought to think slavery could have been re-established.

Well, slavery didn’t come back, but the process of freedom kept going on after the 13th Amendment and Juneteenth. Likewise, the process of freedom had been going on well before those crucial moments.

THE PROCESS—????

So the 13th Amendment, imperfections and all, can be considered the capstone of the project to eliminate chattel slavery. That project lasted two-and-a-half centuries.

From the moment the first ships arrived in North America with enslaved Africans, there were people looking to take down the chattel slavery system. This system wasn’t fully formed in 1619. After all, a few Africans in the first wave of slavery in North America managed to obtain their freedom. By 1700, though, Virginia and other colonies had explicitly and legally linked the idea of blackness to enslavement; the idea of perpetual bondage for a race of people.

And during the colonial era, Native Americans, especially in the Carolinas and New England, were often captured and sold into slavery too. The de facto enslavement of Native Americans was also a horror in colonial Spanish New Mexico and later in American California.

During the Civil War, Black action, local officials, and federal pressure were able to convince Missouri and Maryland, two states exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, to pass state laws ending slavery. West Virginia only joined the Union during the war under the condition that they also end slavery.

This is why I want these sports teams, corporations, and everybody to take a deep look at themselves and their local histories.

What happened in your city, your state, your region concerning slavery and emancipation?

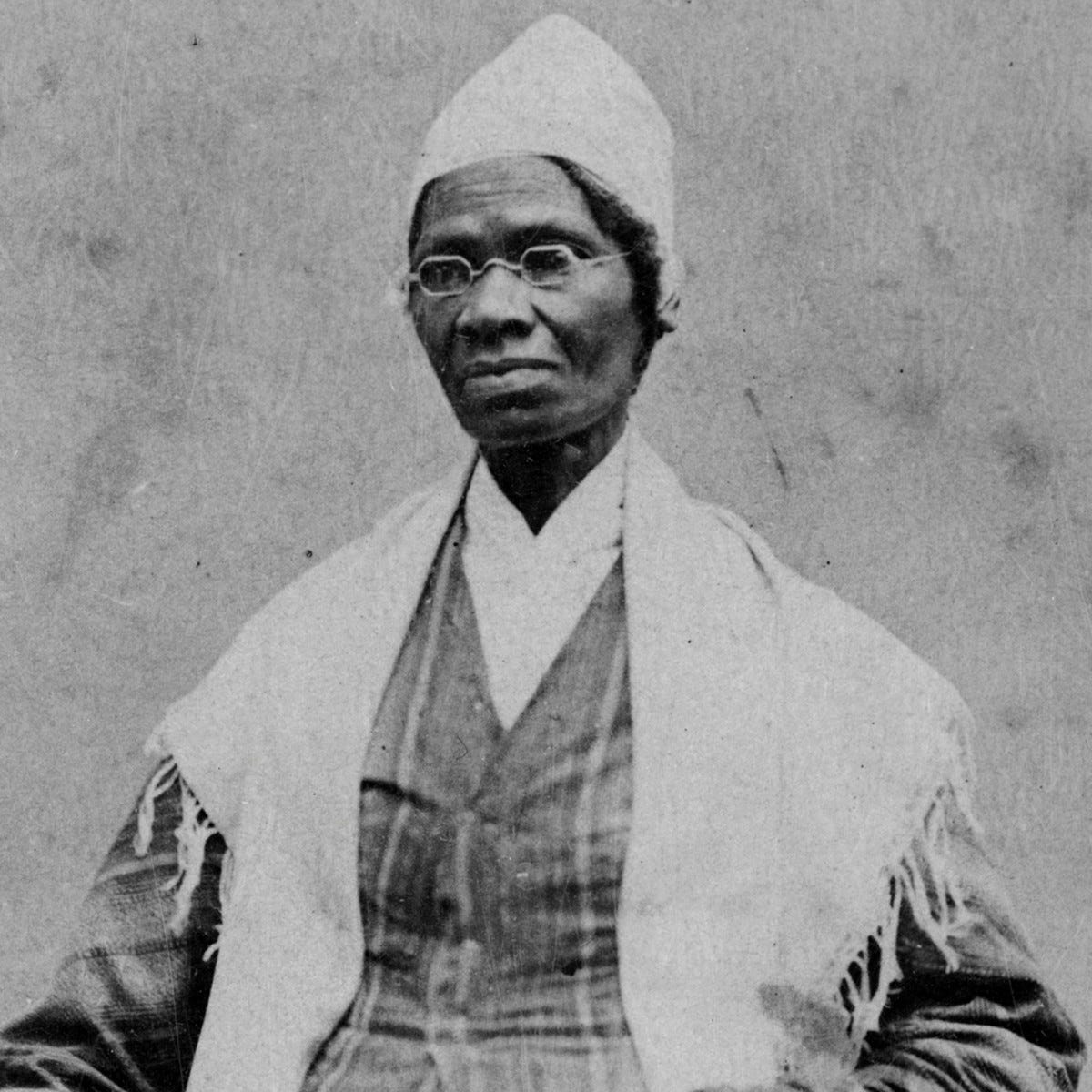

Sojourner Truth—born enslaved in New York State

Well, to help y’all along that path, to appreciate the process, below is a brief legal summary of emancipation for the United States. (As I’ve shown already, people like Louis Hughes and Jake Wilson put flesh and bones on the process.)

Also, it was common for emancipation to be followed by other legislation meant to restrict the civil rights of Black people. For example, when Oregon banned slavery, they also banned Black people from the state entirely. Or when Ohio squashed slavery, they made any free Blacks who settled in the state post a bond to ensure “good behavior.”

But away we go for the states that were part of the United States during the Civil War period. Sorry, Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Marianas, Virgin Islands, and American Samoa.

Here are the big pieces of legislation that covered multiple states and territories.

Northwest Ordinance—July 13, 1787. Banned most forms of slavery in the old Northwest Territory.

An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States—June 19, 1862. Outlawed chattel slavery in all territories (current and future) of the United States.

Emancipation Proclamation—January 1, 1863. Declared “persons held as slaves” were forever free in most of the rebellious states, however, it did not legally end the institution of slavery.

13th Amendment—December 18, 1865. Legally ended chattel slavery throughout the United States. It was ratified by the requisite number of states on December 6, 1865. I’m choosing December 18 as the date because that’s when the secretary of state officially certified the ratification process was over.

And now the locales!

(Please note that some of these dates, especially when not tied to national laws are admittedly not 100% precise. States/territories might pass a law one day, but not have it take effect until later. I’ve not always been able to find the implementation date. Also, other states that did gradual emancipation did not always track when the final person was freed.)

Alabama—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

Arizona—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

Arkansas—January 1, 1863, through March 16, 1864. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended by new state constitution when Unionists regained control of the state during the Civil War.

California—1850, through December 18, 1865. Technically admitted as a free state via the Compromise of 1850, but de facto enslaved Native Americans via the farcically named Act for the Government and Protection of Indians.

Colorado—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States

Connecticut—March 1, 1784, through 1857. The state’s Gradual Abolition Act of 1784 declared black children born to enslaved parents after March 1, 1784, would be freed upon their 25th birthday. A subsequent law in 1848 emancipated the last of these persons awaiting freedom under the 1784 law and its 1797 amendment. However, the last enslaved person (Nancy Toney) in Connecticut died in 1857 since they were not subject to any of these laws.

Delaware—December 18, 1865. Slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

District of Columbia—April 16, 1862. Congress passed a law immediately abolishing slavery, but provided financial compensation to the erstwhile masters.

Florida—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

Georgia—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

Idaho—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

Illinois—July 13, 1787, through April 1, 1848. Ostensibly subject to the Northwest Ordinance, territorial and then state officials tolerated instances of slavery until the state ratified its 1848 constitution, which explicitly banned slavery.

Indiana—July 13, 1787, through July 1820. Ostensibly subject to the Northwest Ordinance, territorial governors tolerated slavery. The state’s 1816 constitution banned slavery, but not until the Polly v. Lasselle case in 1820 did the state crackdown on slavery. Nonetheless, the 1840 census listed three slaves still residing in Indiana. Not sure when those persons were freed. The 1850 census showed no slaves in Indiana.

Iowa—March 6, 1820. Missouri Compromise banned slavery in the then-territory, but wouldn’t surprise me if officials overlooked instances of slavery like they did in neighboring territories.

Kansas—February 23, 1860. The anti-slavery territorial legislature passed a bill outlawing slavery over the pro-slavery governor’s veto capping the tumultuous Bloody Kansas years of the 1850s.

Kentucky—December 18, 1865. Slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

Louisiana—January 1, 1863, through September 5, 1864. Most of the state was subject to the Emancipation Proclamation. Unionists passed a new state constitution in 1864 outlawing slavery.

Maine—1781 through 1783. As part of Massachusetts slavery was ended. Status as a “free” state reaffirmed in the Missouri Compromise.

Maryland—October 13, 1864. New state constitution abolished slavery.

Massachusetts—1781 through 1783. In a trio of court cases, the Massachusetts Supreme Court held that slavery was incompatible with the state’s 1780 constitution effectively outlawing the institution.

Michigan—July 13, 1787, through October 6, 1835. Like its old Northwest neighbors, Michigan tolerated slavery throughout its territorial status despite the Northwest Ordinance. Finally in 1835, upon admission to the Union, Michigan’s constitution banned the institution.

Minnesota—July 13, 1787, through October 13, 1857. Another example of the old Northwest tolerating slavery until a constitution was adopted in preparation for admission to the Union.

Mississippi—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

Missouri—June 1863 through June 6, 1865. An initial provision adopted in June 1863 began gradual emancipation to be completed by 1870. Subsequent state constitution adopted in 1865 provided for immediate emancipation.

Montana—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

Nebraska—January 1861. Territorial legislature overrode the governor’s veto and outlawed slavery. Cannot find a specific date when the legislation took effect.

Nevada—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

New Hampshire—December 18, 1865. Practically speaking, slavery had vanished from New Hampshire by the 1850s. Legally speaking, though, the state never explicitly outlawed the institution. So, the 13th Amendment it is.

New Jersey—February 15, 1804, through December 18, 1865. The state passed a gradual abolition law in 1804 that was so feckless that there was still about a dozen enslaved people in 1865 when the 13th Amendment ended chattel slavery.

New Mexico—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

New York—July 4, 1799, through July 4, 1827. New York’s gradual emancipation law went into effect in 1799. A subsequent law freed the last remaining enslaved people on July 4, 1827.

North Carolina—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

North Dakota—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

Ohio—July 13, 1787, through November 29, 1802. Another Northwest territory carve out. The 1802 constitution officially forbade slavery.

Oklahoma—1866. Remember this was Indian Territory at the time. Treaties negotiated in 1866 between the United States and the Nations of Indian Territory abolished slavery within the territory.

Oregon—1843 through November 7, 1857. During its territorial stage, Oregon tolerated instances of slavery, although the territory was generally hostile to slavery and black people. The territory’s statehood convention finally, irrevocably banned slavery in 1857 while maintaining the laws excluding free blacks.

Pennsylvania—March 1, 1780, through 1847. The first state to pass a gradual abolition law. A subsequent law in 1847 liberated the final handful of remaining enslaved people.

Rhode Island—February 1784 through 1843. Another state with a gradual abolition law. And another state adopted subsequent legal statute—a new constitution—to finally end the institution after decades of waiting.

South Carolina—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

South Dakota—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

Tennessee—February 22, 1865. Adoption of new state constitution during the Civil War.

Texas—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

Utah—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

Vermont—July 1777. The self-proclaimed independent state legally abolished slavery with its constitution. However, like you’ve been noticing, enforcement often lapsed with reports of instances of enslavement lasting into the early 1800s.

Virginia—January 1, 1863, through December 18, 1865. Subject to the Emancipation Proclamation; slavery legally ended with the 13th Amendment.

Washington—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

West Virginia—April 20, 1863, through February 3, 1865. Initially West Virginia adopted a gradual emancipation plan that would have been as drawn out as those of the Northeast states. However, as the Civil War neared its end and the 13th Amendment was winding its way toward ratification, the state instituted immediate emancipation in 1865.

Wisconsin—July 13, 1787, through February 1, 1848. Another old Northwest state that lumbered through a state of technically outlawing slavery as a territory, but not fully suppressing the institution until statehood.

Wyoming—June 19, 1862. Subject to An Act to secure Freedom to all Persons within the Territories of the United States.

Thanks for writing this, Curtis. Very well done and educational.