Previously, we checked out the “amateur” career of Babe Didrikson. That stage of her sporting life came to an end in December 1932 when the AAU banned her because of a Dodge automobile advertisement. Didrikson also lost her day job at the Dallas insurance company that employed her thanks to the fracas.

The timing of the AAU ban couldn’t have been worse bsketball-wise. December 1932 was basically the beginning of the 1932-33 hoops season. Fortunately, Babe was undaunted. In January 1933, the Texan appeared with the Brooklyn Yankees, a women’s team in New York.

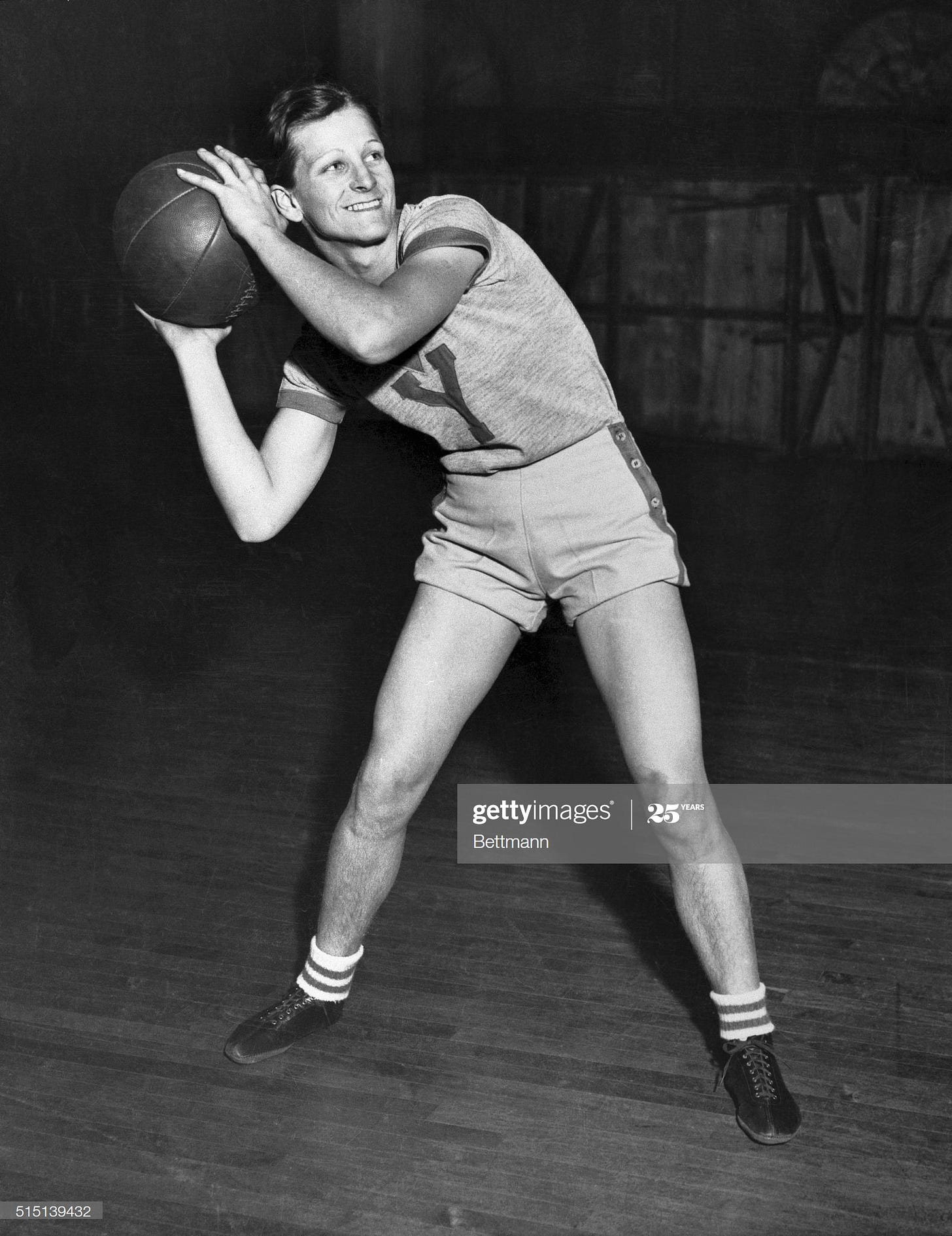

Babe practicing with the Yankees

“Everything that was ever said in praise of Babe Didrikson’s basketball ability still goes,” gushed Lou Niss of the Times Union paper of Brooklyn on January 14, 1933.

The Texas Tornado is good. There is no getting away from it. Hereafter, if any one should tell this writer that Babe is the best puddle jumper in the world he will take it for granted. She proved last night that her fame as a courtster was not unfounded when she led the Brooklyn Yankees to a 19 to 16 victory over the Long Island Ducklings at Arcadia Hall.

Niss found only one failing in Didrikson’s play: defense. It was an unsurprising defect. He noted that in women’s AAU basketball “only the forwards are allowed to score, the guards do the defensive work and the forwards concentrate on scoring and nothing else.” The court was literally divided into zones and forwards like Babe were allowed only to play near the opponent’s basket, since their job was to score. Didrikson had great speed to make up for defensive mistakes she made, however, according to the reporter.

Her offensive game, of course, was fantastic since the AAU brand of ball had essentially specialized her to the task. “She passed the ball with the speed and accuracy of a man,” was one sexist form of praise given to her. She scored nine of her team’s 19 points including two points on “a heave half the length of the floor.”

Niss concluded his column noting that “a great ovation from the hardboiled fans” was given to Didrikson and that “to the credit of the Olympic champion it must be admitted that her appearance marked one of the very few times in which a ‘big’ name lived up to advance notices.”

Well, this isn’t definitive, but I cannot find any subsequent game action of Didrikson with the Yankees. Furthermore, a quick Associated Press report from January 26 noted that Didrikson “was ordered to bed by her physician” and here manager, George Emerson, said she “evidently is tired out from her heavy schedule the past few weeks.”

So that seems pretty much it for Babe in the 1932-33 season. The next time I can capture Didrikson in the basketball record is the fall of 1933.

BABE’S ALL-AMERICANS

In September ‘33, Didrikson signed a contract with Iowan Ray Doan to organize and promote a new troupe of mostly male barnstormers to begin play in November. Sure enough the AP on November 10 carried the news of a “mixed basketball team, headed by Mildred (Babe) Didrikson” that would begin training in two weeks.

The first documented game action I could find of the squad chronicled their December 1 match in Moline, Illinois, against an all-star team of local men’s players. They lost to the all-star squad of men, 36-30. Didrikson was the only woman to play in the game and scored two points.

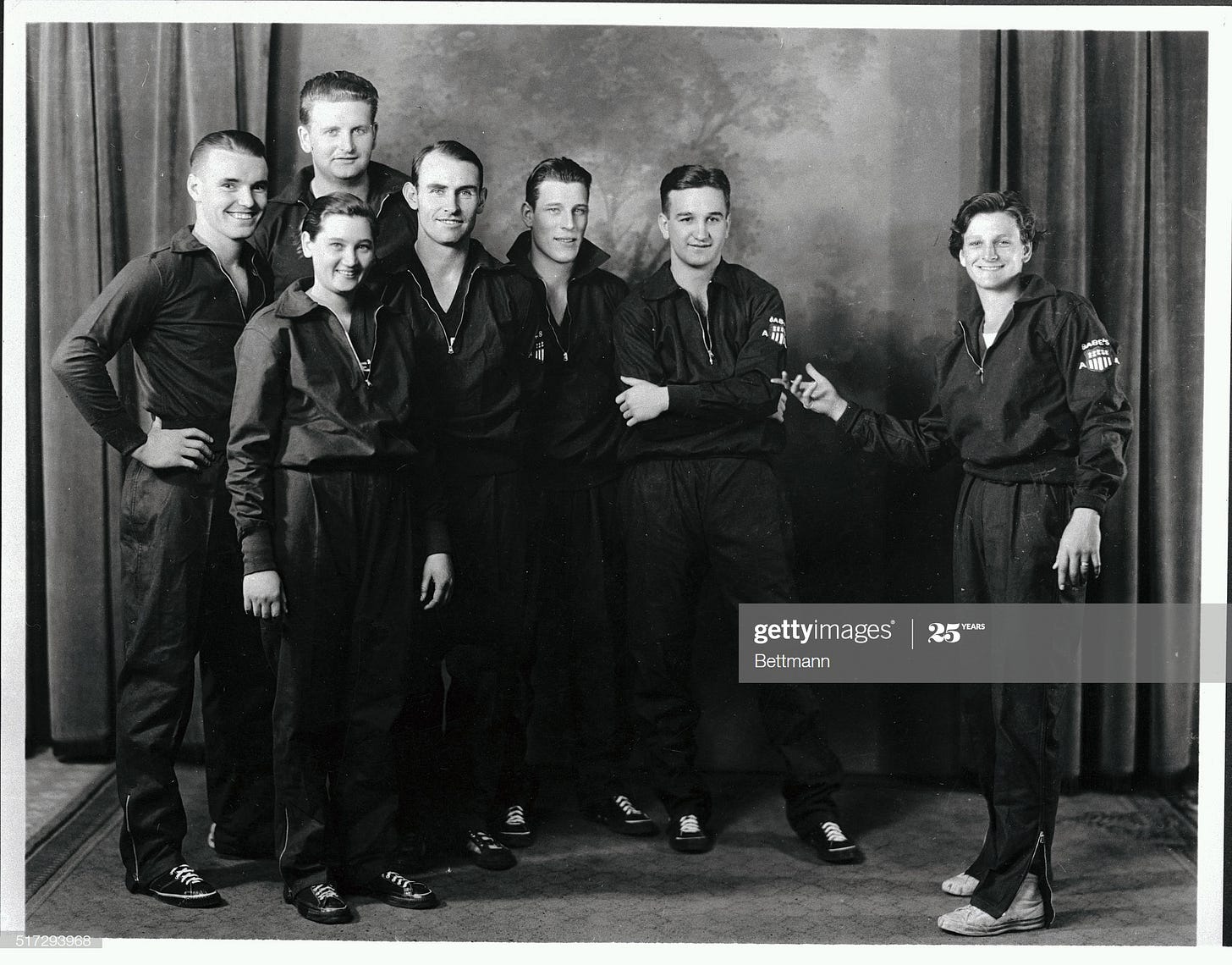

Photo of Babe’s All-Americans in November 1933. Left to right they are William McIntyre, Jackie Mitchell, Bob Shafer, Lefty Byers, Dick Butzen, and Darrel Darby.

Didrikson wasn’t the only woman on the All-Americans, though. Jackie Mitchell appeared as a permanent fixture with the team even though the male players appear to have cycled slightly during the season.

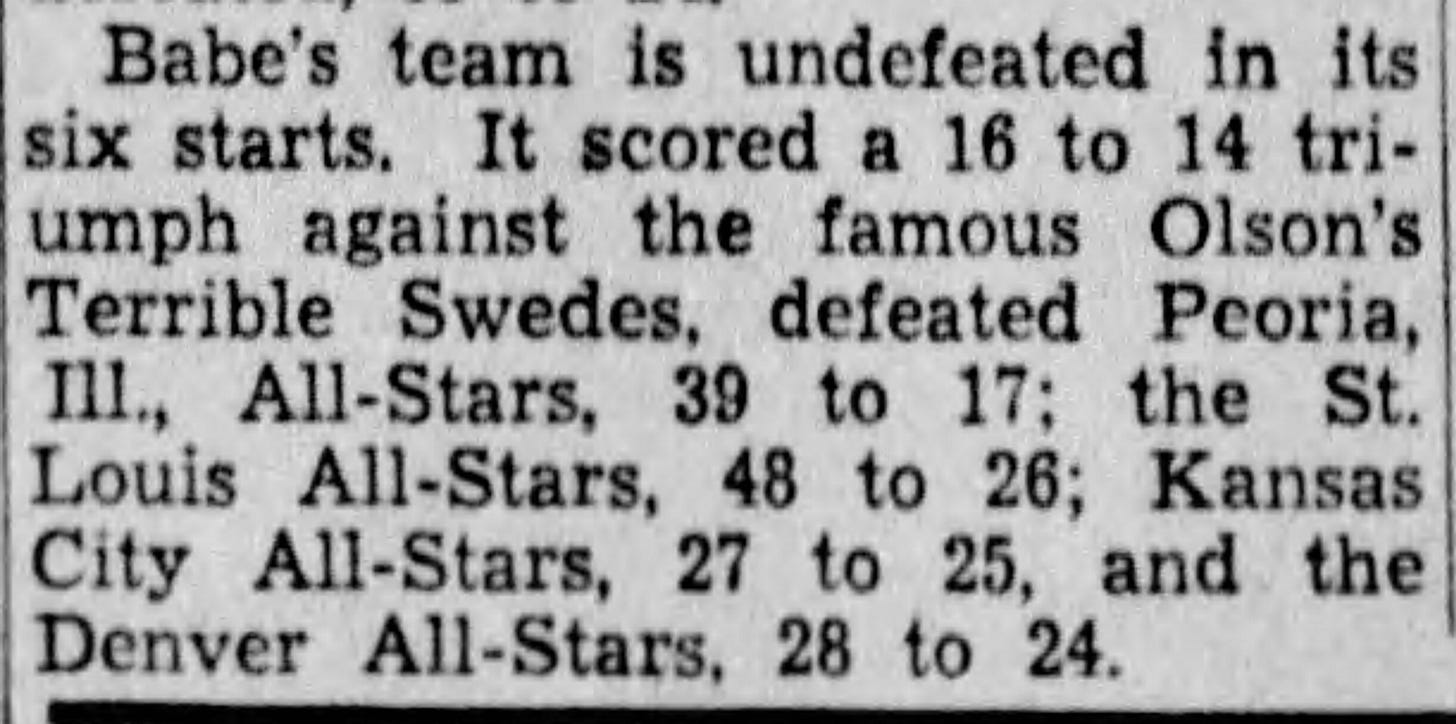

By December 15, Babe’s All-Americans were hailed as an undefeated squad by the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Showing how hard it is to track barnstorming teams, the Star Tribune’s tally of games played did not include the game—a loss—that I found from Moline. Anyhoo, here’s the rundown from the MPLS paper…

And the Star Tribune had Didrikson down for 45 points over the six games for an average of 7.5 PPG. Not bad considering her team’s average score was 32.2 PPG. Just days after the Minnesota report, the All-Americans lost 32-31 in South Dakota to Rex Stucker’s Rock Springs Sparklers… take a moment to appreciate that name…

All in all a good start to the basketball season for the “mixed” club that was thrown together at a moment’s notice.

Entering the new year of 1934, Babe’s cagers appeared in Bucyrus, Ohio, on January 8, 1934. The local paper, the Telegraph-Forum, was highly excitable in the days leading up to the game. Didrikson was called “the world’s greatest woman athlete,” while her teammate Jackie Mitchell was praised as a “baseball hurler” who once struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in an exhibition.

Then there are Darrall [sic] Darby, formerly with Kentucky university; Lefty Beyers [sic], all Missouri star with the Kansas Aggies; Carl Howard, formerly with Olsen’s Terrible Swedes; Dick Butzen, Loyola star and Bob Shaeffer [sic], six foot, six inch giant who tosses them in from under the basket effortlessly.

The gender-mixed squad would prove to be a hit with men and women, the paper predicted.

A large crowd of girl athletes is expected to attend this game to see the woman who set the world aflame with her dazzling performances. The men will gather to see one of the best basketball games this town has had in several years and all in all it looks like a gala evening.

Although predicting the All-Americans would have a tough time with the Sinclair Oilers, the Bucyrus paper thought Babe’s squad would win the day. Well, that’s why we play the game. The Oilers upset the All-Americans, 30-26.

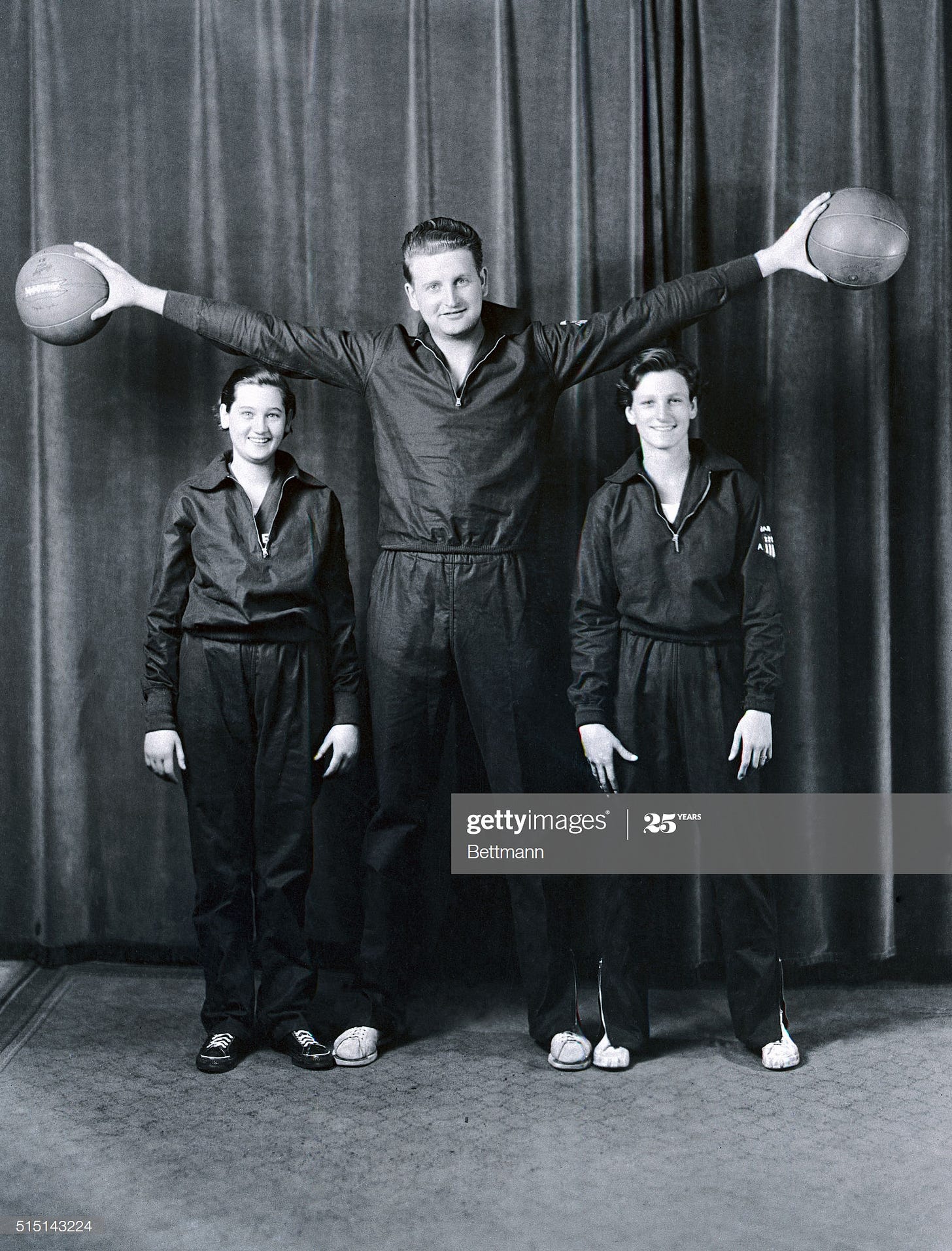

Mitchell, Shafer, and Didrikson

John W. Saffell of the Telegraph-Forum interviewed Didrikson after the game. Since she had a subpar performance, Saffell assumed she must be worn ragged from all the traveling required of barnstorming. Not an unreasonable assumption given that this was an era where barnstormers typically drove to their games and the All-Americans had gone through Colorado, Iowa, South Dakota, Illinois, and Ohio.

Somewhat evading the question of travel fatigue, Didrikson insisted she liked being out on the road.

“It’s really a lot of fun, traveling over the country playing basketball. After all, athletics is my life and unless I am actively engaged in some sort of sport I feel restless. And it’s really not so bad as some people think. We get a good night’s rest every night, but of course we must sometimes sleep until noon of the next day to do it. Nevertheless the association with the many people I meet on my travels is interesting and worthwhile.”

A couple weeks later (Jan. 19) Babe and the All-Americans rolled through central Pennsylvania and defeated the Harrisburg Senators, 38-32. She scored seven points and customarily impressed the local reporters. “She is however a great leader and demonstrated it last night in her wonderful floor play, clever passing” was how the Harrisburg Telegraph assessed her play.

In early February, Didrikson gave one helluva interview lauding her team. She also was indignant at the idea that women should only play women. I suspect her forceful answers were a result of the limitations placed on women’s basketball. There was virtually no professional outlet and the amateur variety, as discussed already, confined women to specific zones of the court. You couldn’t really show your full talent or develop all-around skills that way.

(Also by this point, it appears that Mitchell had departed the club.)

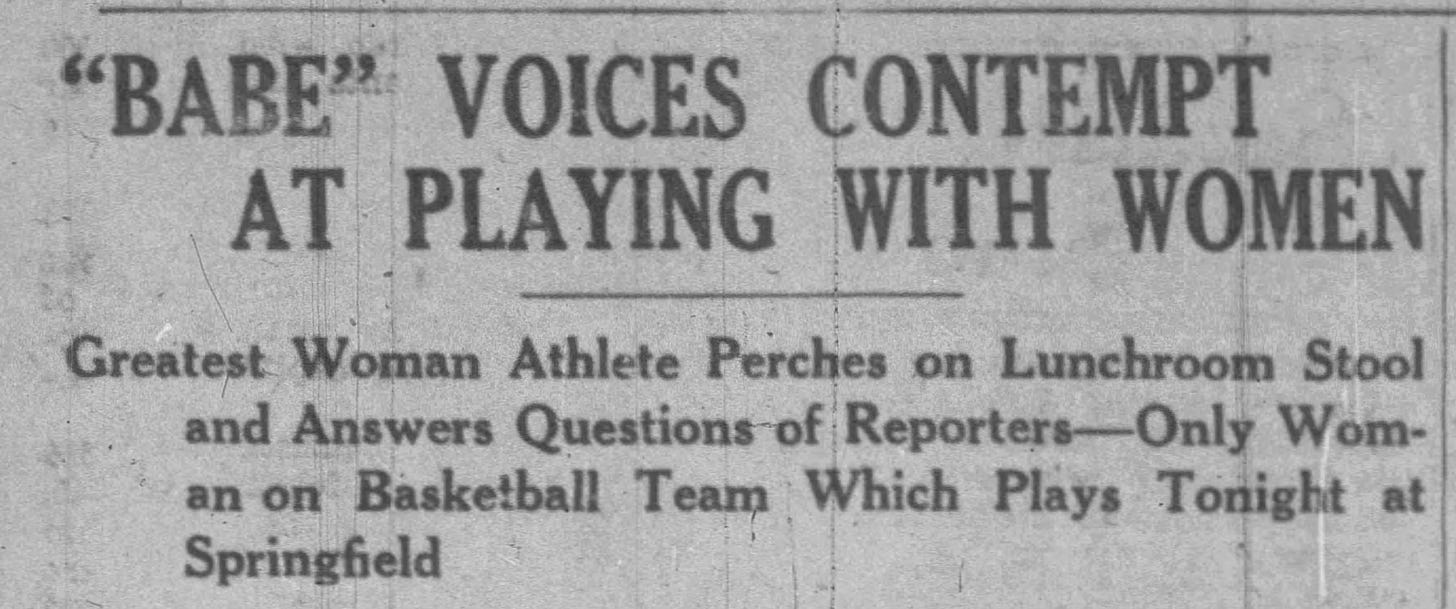

Berkshire County Eagle, February 7, 1934

So, the interview happened as the All-Americans were on their way to a game in Springfield, Massachusetts. The team was eating in a diner as a Berkshire County Eagle reporter started peppering Didrikson with questions.

“I have my own team,” Didrikson proudly told the journalist seated with her. “Babe Didrikson’s All Americans.” “I suppose it’s a woman’s team,” the reporter assumed.

“Of course not,” was the rather contemptuous reply. “I’m the only woman on it.”… No she doesn’t find it difficult to play men’s basketball against men. “Of course, you have to get used to it,” she admitted, “and you have to be a lot more active than in the woman’s game. But I like it better.”

The reporter, writing in the third person, continued being a naive waif in the presence of the Babe. In fact, he seemed unaware of what female athleticism was and could be.

The reporter was struck by the comparatively slight figure of Miss Didrickson, whom he had always imagined to be something of an Amazon. Doesn’t she find herself at a disadvantage in competing against heavier women? “No,” she said. “That makes ‘em slow. I can run circles around them—and most men, too.” Somehow, there seemed no point in challenging her word.

With 40 men perched on nearby stools, the reporter found it difficult to question this woman who could beat him in a hundred-yard dash, score through him on the basketball court and outdrive him at golf. “Have a glass of beer?” he offered in desperation. “No,” she said, “it slows me up.”

A few moments later, they left—Miss Didrickson and her six collegiate stars. “That lunch set me,” she told the reporter as a parting thrust. “I’ll bet I make six goals tonight.” Bewildered and somehow depressed, the reporter finished his own beer and paid the check. He felt quite “slowed up” as he walked back to the office.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any record of how Babe did in the upcoming Springfield game. In fact, the All-Americans in the historical record that I have access to pretty much fall off the map after this Massachusetts story.

Well, this was barnstorming in the Great Depression. Easy come, easy go. And the All-Americans were centered on a star player who loved to try her hand at any and all sports. If the All-Americans simply played out the basketball season never to be heard from again, it wouldn’t surprise me.

At the ripe old age of 23 Didrikson was pretty much done with basketball. Her play with the All-Americans against men helped set the stage for future women barnstomers like the All-American Red Heads. Another story for another day, right there.

Anyhoo, Babe Didrikson—later known as Babe Didrikson Zaharias after her marriage to former wrestler George Zaharias—by the late 1930s found her greatest professional success in the world of golf.

If only basketball provided the same outlet at the time.