In my conversation with Helen of Women’s Hoops Blog, we talked about how early opportunities for women to play competitive basketball for money came via industrial and Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) teams. Technically, these players weren’t professionals because they were paid to work at a company. It just so happened these companies also fielded sports teams for recreation. And advertisement. And trophies.

Walks like a duck… quacks like a duck… but not a duck.

Anyhoo, many great basketball players, men and women, got their start in this model of play.

Today we look at one such star, who might be the greatest athlete ever. She seemingly wanted to play every sport as chronicled in this Alton Evening Telegraph interview from January 18, 1932:

“My favorite sport? Say. I’m sorry, but I don’t have one,” she said. “The best way to take athletics is to like them all.

“My favorite hobby? There is no such thing. Athletics are all I care for. I sleep them, eat them, talk them, and try my level best to do them as they should be done. You’ve got to feel that way.”

That’ll be Mildred “Babe” Didrikson!

CYCLONE TROUBLES, BABE TO THE RESCUE

Melvin Jackson McCombs was the Dallas Employers Casualty Insurance Company’s athletic director. His official job with the company was managing the farm and tornado divisions. Given his whirlwind portfolio, McCombs’s teams were dubbed the “Golden Cyclones.”

Well, things weren’t so golden in basketball. McCombs was peeved that the rival Sunoco Oilers—also based in Dallas—outpaced them and won the AAU women’s basketball title in 1929. The Cyclones lost to the Oilers by a single point. After consistently being bested by the Oilers and barely losing to them for a title, McCombs wanted to win the 1930 AAU tournament come hell or high water.

He hit the road to scout down in Houston where he encountered the Babe.

[Ed. note: You’ll see that newspapers in the 1920s/30s consistently misspelled Didrikson’s name as “Didrickson.”]

Now Didrikson wasn’t from Houston. Her hometown was Beaumont, some 70 miles or so to the east near the Texas-Louisiana border. Still a teenager, Mildred was the star of her high school team, the Miss Royal Purples. Heck she seemed to star in whatever sport she laid eyes and hands on.

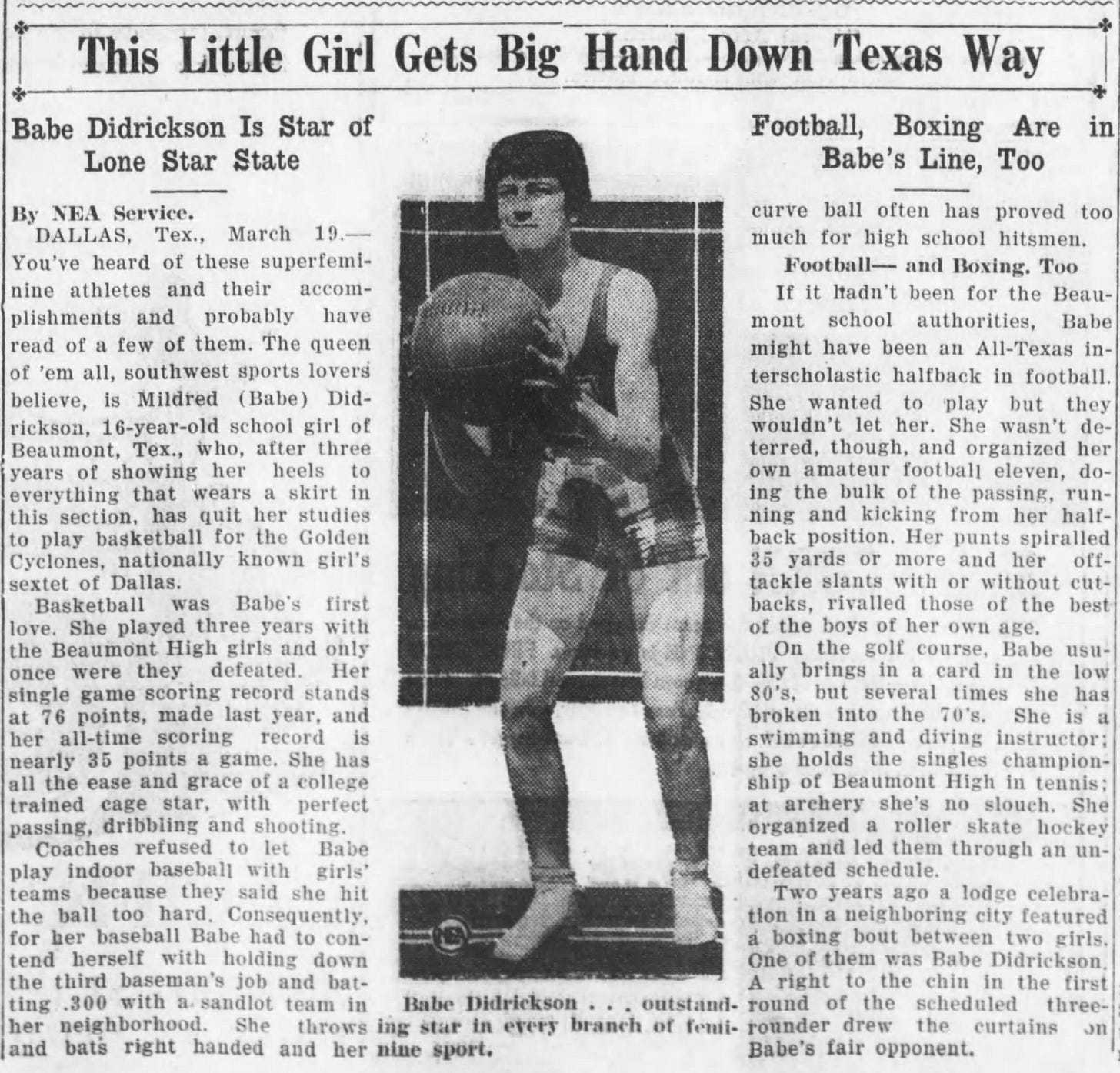

Santa Cruz Evening News, March 19, 1930

According to Joanne Lannin in her fantastic book Finding A Way to Play, Didrikson’s high school team didn’t lose a game between 1927 and 1930. And if you bothered to read that news clipping right above yonder, you’d see the Babe once scored 76 points in a game. That’s patently absurd in any basketball game of the era given the rules of the time.

Well, Mildred “only” scored 26 points in the game she played in Houston that McCombs attended. Good enough for him. He offered Didrikson a clerical job paying $900 a year at the insurance company, which would make her eligible to play for the Golden Cyclones. Her parents agreed to let the 19-year-old Didrikson skip the last couple months of high school to join the team.

Okay, so back to the rules of basketball at this time.

Women’s basketball courts was divvied up into sections and players assigned to each zone. Men’s basketball had fooled around with such notions in the 1890s and early 1900s, but had largely ditched the concept for a more open, free style. Still shackled to notions of “female fragility”—women supposedly couldn’t handle the strain of running the full length of the court—women’s basketball still had the zones. In high school it was usually three. A team would keep its best scorers in the zone near the opponent’s basket, while keeping the best defenders near their own.

Well, in the AAU, women only had to contend with two zones, which was a change of pace for Babe. Albeit not a huge one apparently. In her first game with the Golden Cyclones she scored 14 points.

The Cyclones proceeded to smash the competition with Babe and met up with their rivals, the Oilers, in the AAU national semifinals. Well, the Oilers again won by one point.

A STAR (AND HEADACHE) IS BORN

Didrikson’s prowess had immediately caught the attention of rival teams, who attempted to poach her away with jobs at their companies. Nevertheless, she remained with the Cyclones for 1931, which finally proved to be their golden season.

On the road to the national tournament, the Cyclones finally ousted their Sunoco nemesis in the AAU’s Southern tournament.

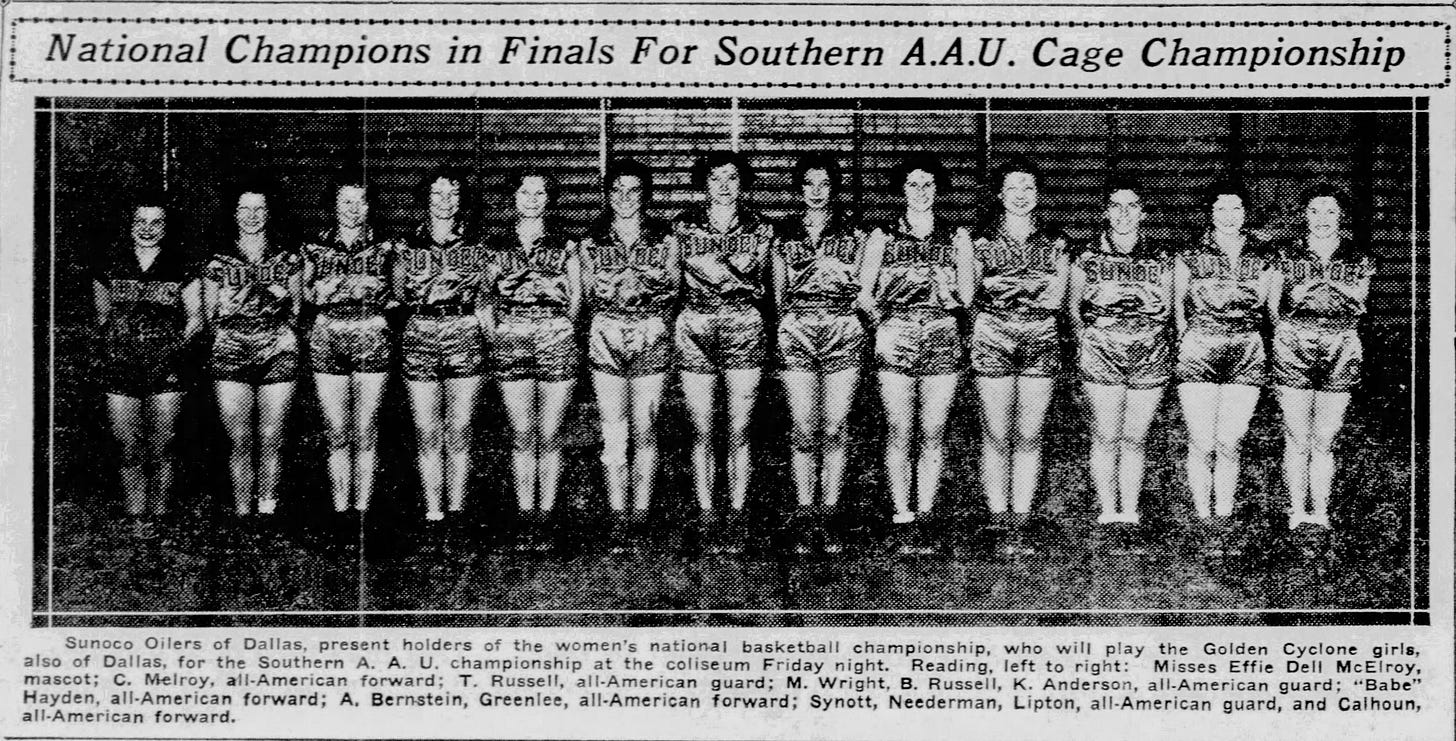

The Sunoco Oilers, Shreveport Journal, March 6, 1931

After coming painfully close to victory in previous years, the gilded outfit throttled their crosstown oil rivals, 31-19, in the tourney final held in Shreveport, Louisiana.

In the national tournament held a couple weeks later, the Cyclones and Oilers appeared headed for a rematch. But just prior to the final game, Sunoco was upset by the Wichita Thurstons, 38-31. Meanwhile, Babe’s squad defeated Crescent College of Eureka Springs, Arkansas, 42-27.

The Thurstons proved no slouch in the championship game. The tight contest ended in positive fashion for Dallas, though, thanks to a Didrikson basket in the game’s final 30 seconds. The Golden Cyclones won the AAU national title by a score of 28-26.

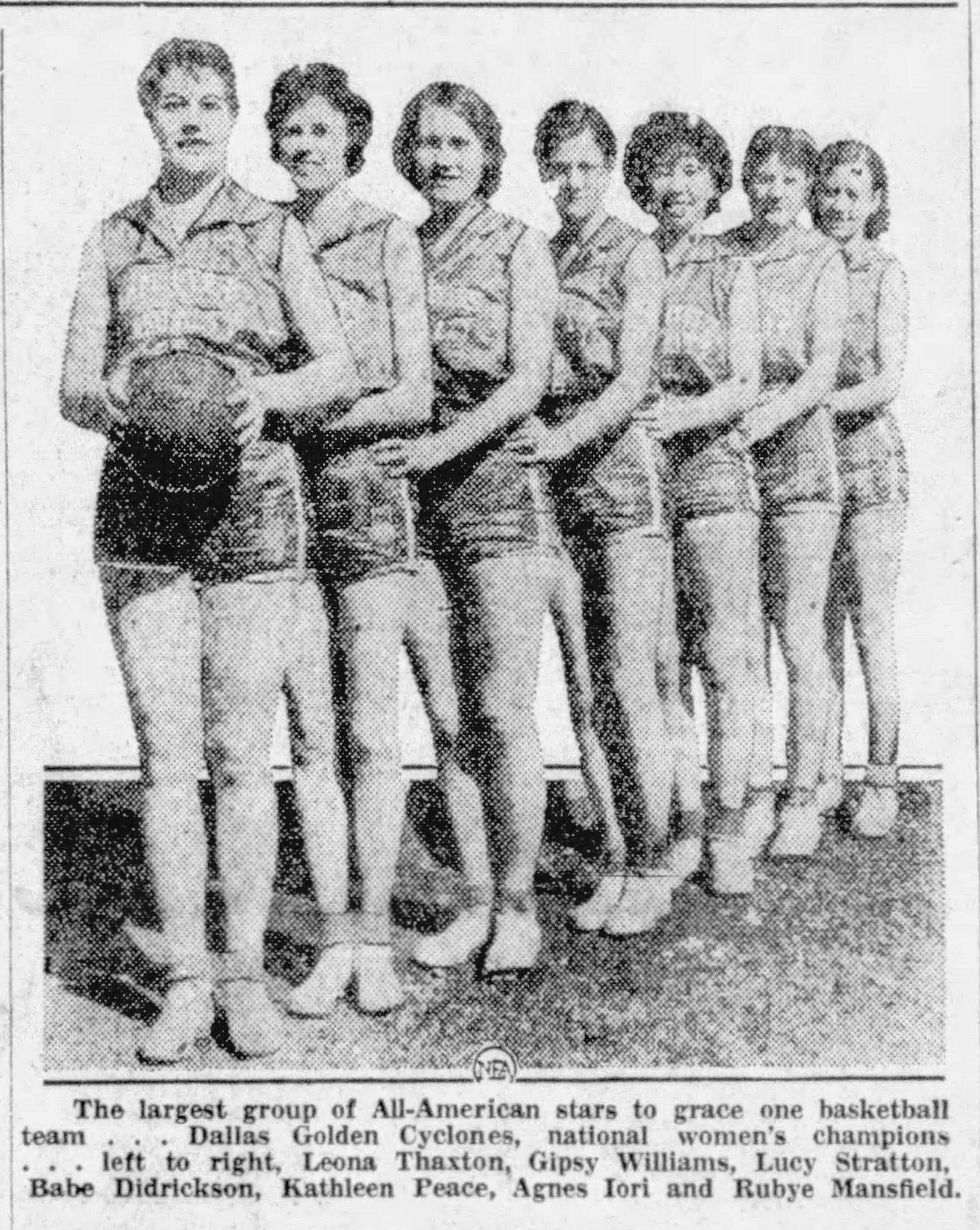

Central New Jersey Home News, February 7, 1932

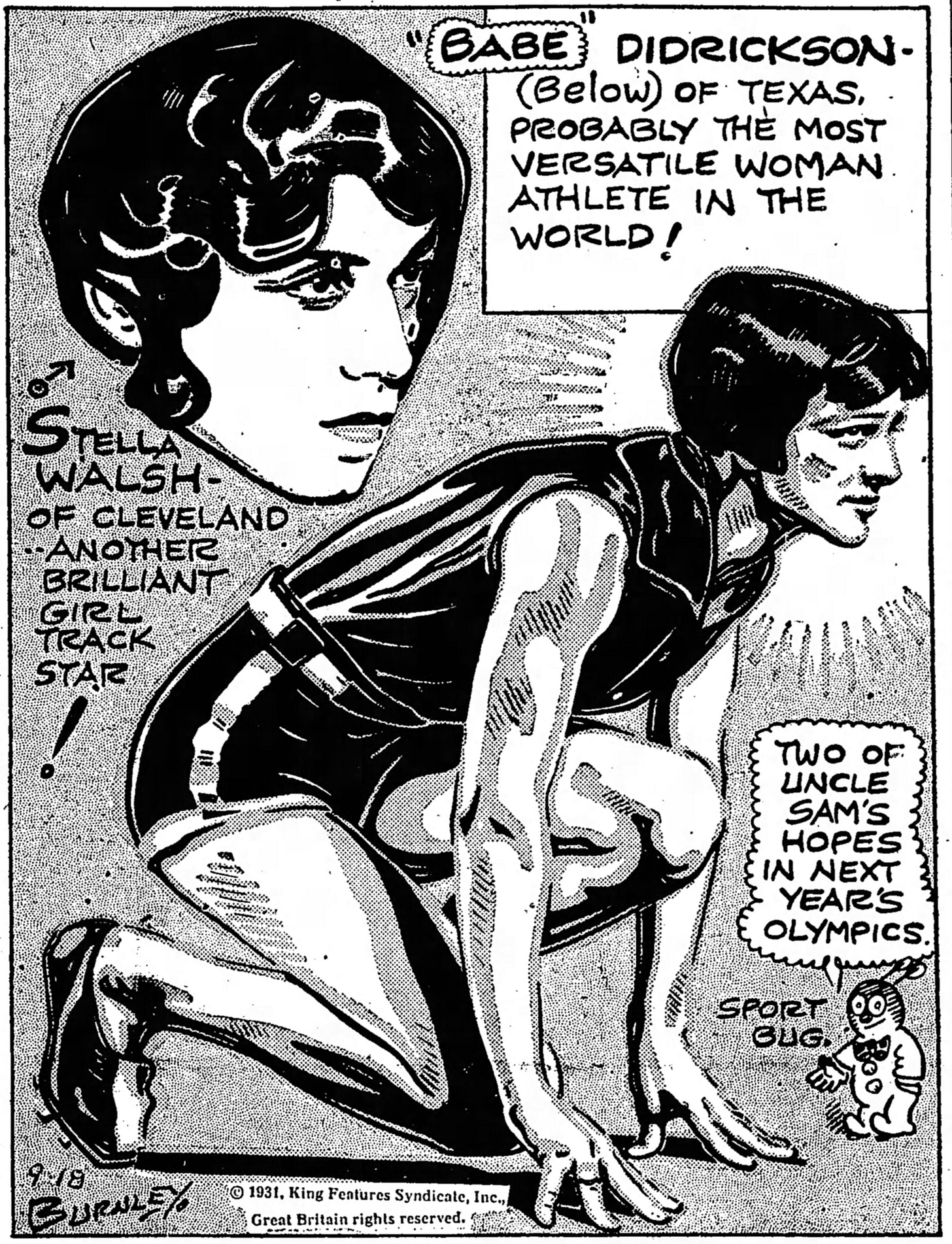

Over that summer, Didrikson continued her athletic marveling as she competed in AAU competitions for hurdles, baseball throwing, broad jump, and discuss throwing. In the fall she was being heralded as a genuine sensation by sports journalist Hardin Burnley:

In many respects, 19-year-old Mildred “Babe” Didrickson of Dallas, Texas, looms as the most extraordinary athlete—man or woman—in the world today and, when her career is ended, she may be a serious candidate for the greatest athlete of all time accolade. This “Babe” is a sprinter, hurdler, broad and high jumper, swimmer and roller skater. She’s a real star in such events and also she shines as a javelin thrower and shot putter. In addition she bowls, plays golf, basketball, and baseball, and (she’s that strenuous) football! Of course, she boxes and those who don the gloves with her believe “Babe” could stop or outpoint half the male amateurs of her weight in six rounds—mirabile dictu!

Corsicana Daily Sun, September 18, 1931

With praise like that, it’s no wonder Babe got a pay increase in 1932 to the tune of $90 a month, instead of the $75 a month she had received previously.

According to Lannin’s history, though, the $90 wasn’t enough for Didrikson.Unsatisfied, she requested yet more money and McCombs’s frustration grew. Cyclones teammates were displeased as well not just with the money, but with how Didrikson didn’t care about strictly adhering to notions of femininity.

Despite the fraying relationships, the Cyclones in 1932 again reached the AAU’s national tournament final. No glory at the end of this road, though. The Cyclones were defeated by Oklahoma Presbyterian College, 35-32. Didrikson scored 16 points in what turned out to be her final tournament for the Dallas Employers Casualty Insurance Company.

END OF AN “AMATEUR”

The summer of 1932 was pretty good for Didrikson. She won two gold medals (80 meter hurdles and javelin throw) plus a silver (high jump) at the Los Angeles Summer Olympics.

However in late September, the Wisconsin State Journal carried a report that she was on the verge of a “nervous breakdown” and “must rest… from two to six weeks, and cannot even receive visitors” according to physicians.

Matters got worse in December when the AAU banished Babe.

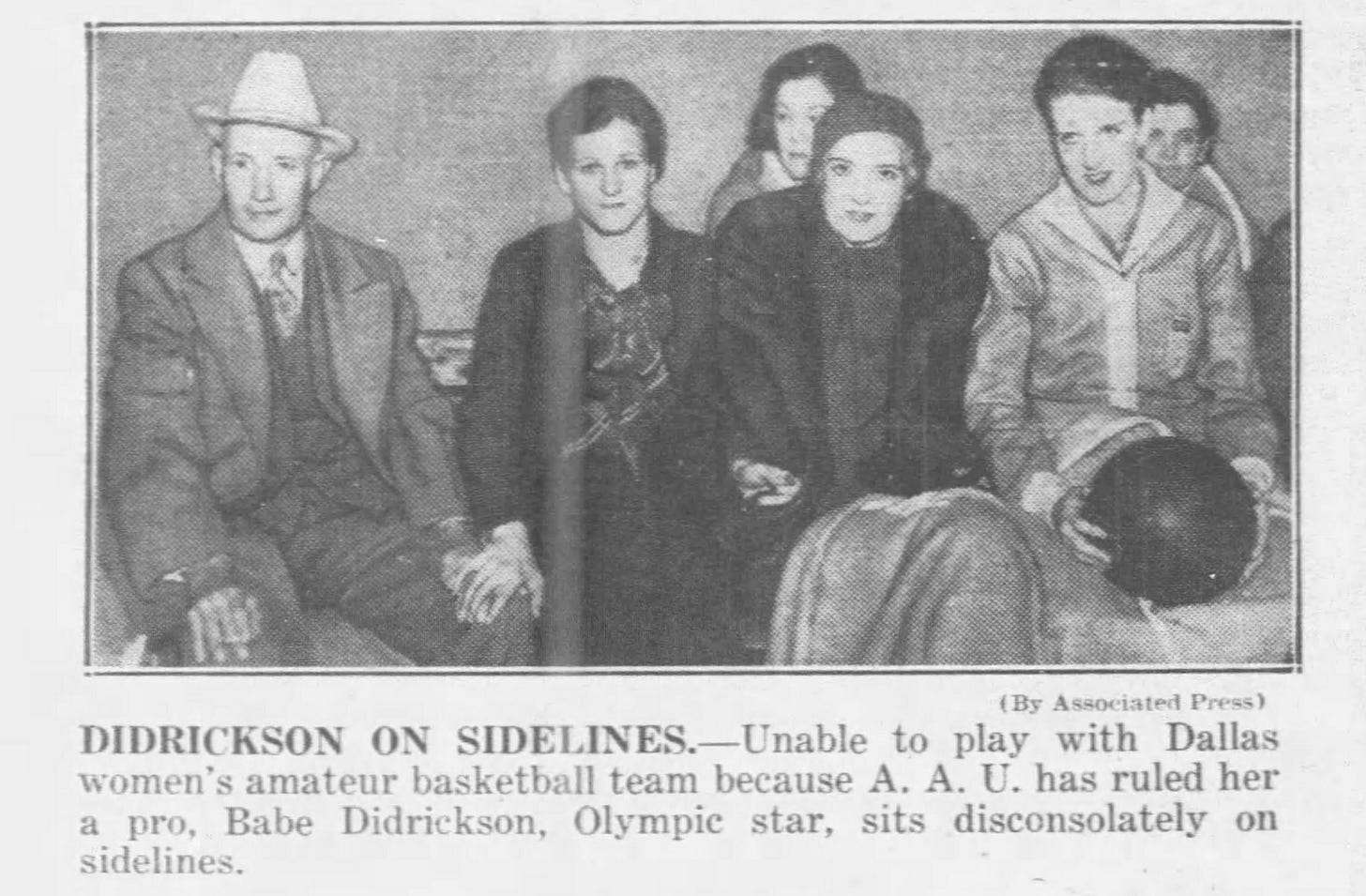

New York Daily News, December 11, 1932

A Dodge advertisement was the source of all the fuss.

I couldn’t find a copy of the ad or when it first published, but by December 6, 1932, the AAU had gotten wind of the situation and suspended Didrikson pending results of their investigation. Didrikson and McCombs denied that she had given Dodge permission to run the advertisement.

The Taylor Daily Press had the scoop in funny fashion:

Miss Didrickson at her home in Dallas, learned of the A.A.U.’s action almost as soon as did DiBenedetto [chairman of the AAU’ Southern branch]. She wasted no time in informing her manager, Col. M.J. McCombs, who wasted even less time in issuing the following statement:

“If Miss Didrickson loses her amateur standing because of the advertisement, which she did not authorize, we will immediately instigate suit against the automobile company responsible for the unauthorized publication.”

Tough talk from the colonel. However, it appeared Dodge and its advertising company had the receipts.

“We have a written letter of release from Miss Didrickson and her manager,” [advertising firm of Ruthrauff & Ryan] told the United Press. “The release gave us full permission to use Miss Didrickson’s picture as well as her comment on the car. It is unreasonable to assume that we would prepare such copy without first gaining full permission.”

Well, events picked up steam quickly.

By December 13, the AAU had completed its investigation and upheld Didrikson’s suspension. She was considered a professional and banned from further AAU competition.

By December 21, Didrikson was unemployed. The Ames Daily Tribune carried a United Press report stating that Employers Casualty removed her from the company payroll. The company claimed she “had cleaned out her desk and departed without a word” for Beaumont. Officially, it seems that Didrikson was “discharged from her filing clerk position in Dallas for being absent without leave,” but it’s hard not to tie the situation to her loss of amateur status.

She was hired by Employers Casualty to play sports. The clerk job was mere window-dressing. Lo and behold! Barely a week after she lost amateur status she’s unemployed. Sure, technically speaking her pay from the company was for clerical work not for playing basketball. But we can connect the dots.

Ah the ruse that is amateurism…

Anyways, Didrikson was done with the amatuer world as much as it was done with her:

“This is my last word concerning my suspension. So far as I am concerned it is a closed incident. Newspapers and the public must be tired of the whole business. I know I am.”

The 1930s were extraordinarily unkind to basketball. The Great Depression nearly strangled to death the pro leagues that men played in. For women it was worse. Several states began to ban or severely restrict amateur tournaments for girls stunting the sports’ growth after four decades of general expansion.

Didrikson hadn’t given up on basketball quite yet, though. The fantastic forward decided to try her hand at barnstorming basketball, free from the strict amateur rules, if not society’s gender gaze.

It’s something we’ll look at very very soon here at ProHoopsHistory.

In the meantime, buy Lannin’s book!

Obviously there’s Amazon, but they’re an evil company. You can also buy a copy from Lannin’s website.